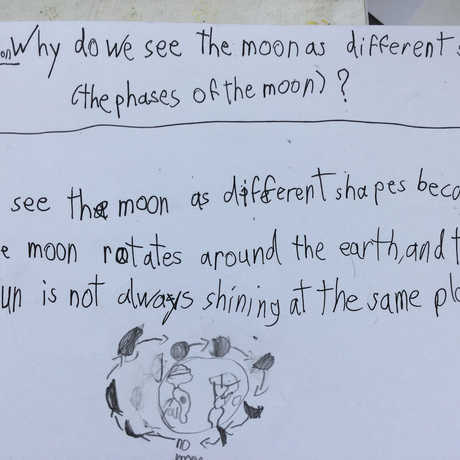

Jinney was preparing for a celery investigation from her 5th grade curriculum. Her students had already experienced a few hands-on investigations, so she didn’t want to just hand them a ready-made procedure. She wanted to give them an opportunity to design the experiment themselves. So, here’s what she did.

To set the stage, she had students discuss a few questions: Are plants living organisms? Are plants made of cells? Are cells alive? How do plants get the resources they need for life? Jinney did not answer these questions – she just encouraged students to talk with each other about their ideas. Then, she showed them the materials they would have at their disposal – celery, pitchers of water, a scale, etc. Finally, she gave them a focus question for the investigation: "Will celery with leaves absorb more water than celery without leaves?" After that, the students were on their own. In groups, they designed investigations to answer the focus question. You can see several of their plans here.