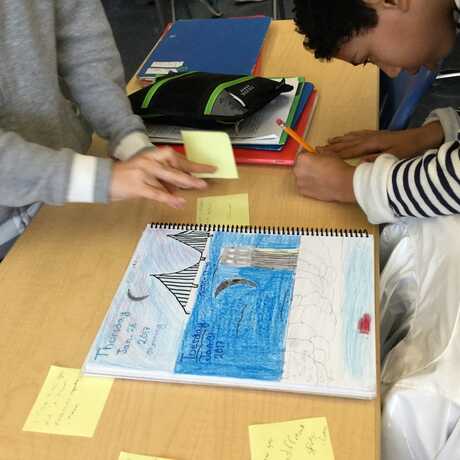

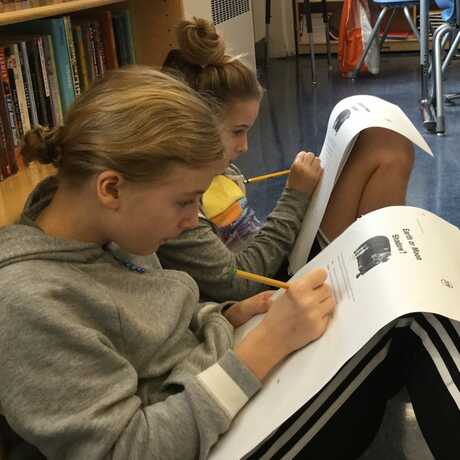

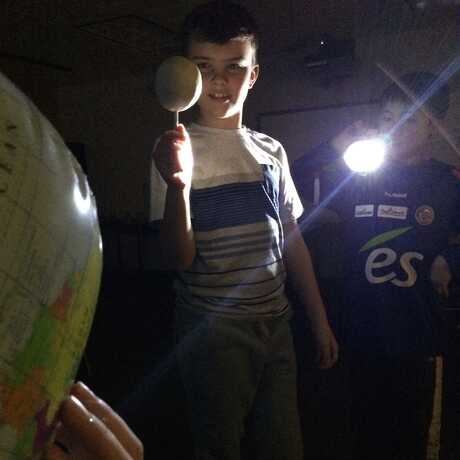

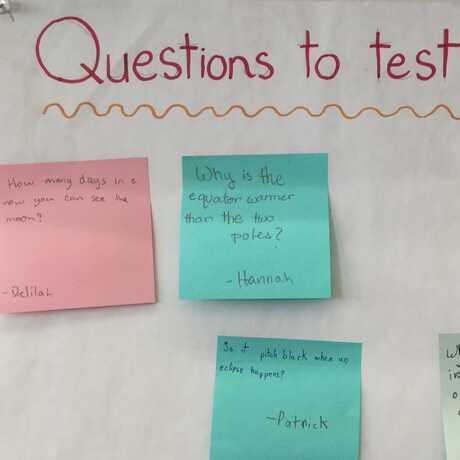

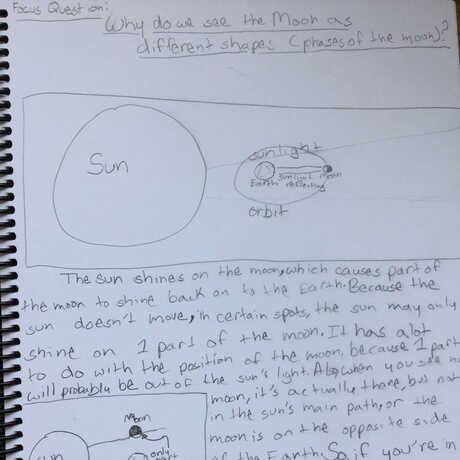

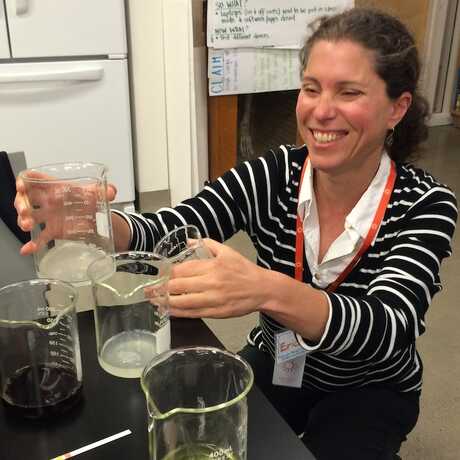

Erica spent a few months exploring phases of the moon with her fifth grade students. She adapted lessons from Lawrence Hall of Science’s GEMS in order to give her students lots of opportunities to answer the Essential Question: Why does the moon look different on different days? Erica’s students used their science notebooks to record observations of the moon, formulate initial ideas about moon phases, and revise their thinking after developing a kinesthetic model.

Read on to see how several notebook strategies worked together to help students build their science ideas. To view examples of student work and to download the complete unit plan, click the links below.