Founded in 1853, the Academy Library is a research library devoted to natural history and the natural sciences. Explore our extensive collections, including rare books, serials, maps, and photography.

Untold Stories

Ynes Mexia

Between cultures

Ynes Enriquetta Julieta Mexia was born on May 24, 1870 and spent her first nine years in the town her family founded, Mexia, Texas. Her father was General Enrique A. Mexia, a diplomat and representative of the Mexican government in Washington, DC. General Mexia was the son of José Antonio Mexia, who served as a Mexican general and was executed for treason in 1839, before Ynes Mexia’s birth. Her mother’s family was American and included Samuel Eccleston, the fifth archbishop of Baltimore. In the 1880s, a young Ynes Mexia moved to Mexico City to live with her father, where she spent much of her childhood after her parents separated. Mexia was privileged in her early life, being born of high status families from both the US and Mexico. She attended private schools in Philadelphia and Ontario and had servants in her large home just beyond Mexico City. Her privilege and monetary means allowed her to pursue her passions in plant collecting later in life, which were largely self-funded.

Life before botany

After two marriages in Mexico, Mexia moved to San Francisco to seek treatment for extreme mental stress and depression in 1908. Mexia’s move to California allowed her to join organizations such as the Sierra Club, California Botanical Society, and the Audubon Association of the Pacific. Excursions with these groups inspired her love of nature and plant collecting. By 1921, Mexia had decided to dedicate her life to these pursuits and began her college degree at the University of California, Berkeley at age 51. In 1922, Mexia went on her first botany expedition to Mexico with UC Berkeley. From then on, she was hooked.

An adventurous collector

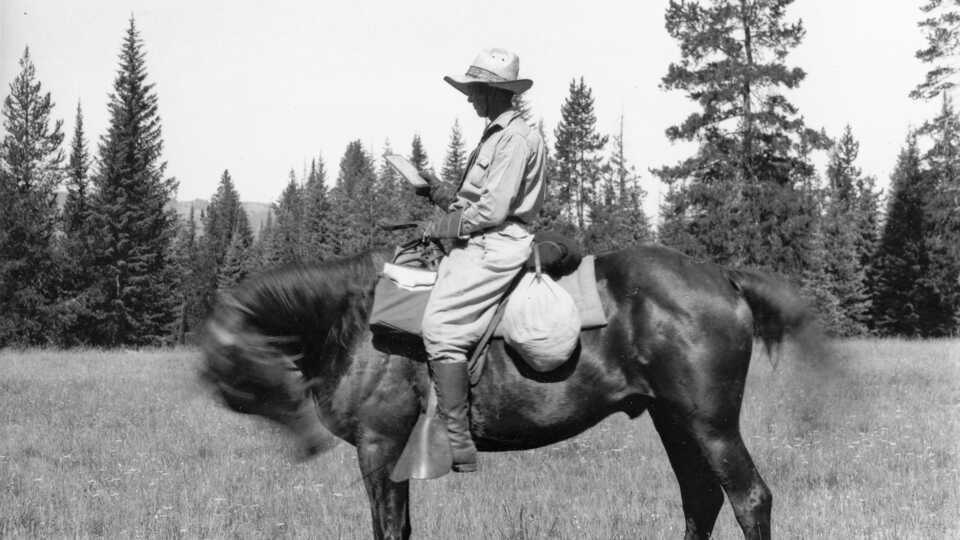

Mexia’s main destinations for major plant collecting expeditions were Mexico and Central and South America. Between 1925 and 1938, just before her death, she went on at least eight months-long expeditions to various locations in these regions. She also conducted the first general collection of flora in Denali National Park and Preserve in Alaska and spent quite a bit of time in the Sierra Nevada, weathering very tough conditions. Thanks to her travels, Mexia became a member of the Sociedad Geographica de Lima, Peru. She was contracted by the California Academy of Sciences to collect plants for botanists at the Academy, and she became a life member of the Academy.

Mexia documented her travels in her own words and photographs. Mexia was an avid photographer in the field with the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, and on her own plant-collecting expeditions. She filled several photo albums that are now in the Academy archives. Her photographs were meticulously labeled, sometimes with amusing notes such as, “A friendly chat” captioning a photo of two quails.

Mexia was not keen on handling the plants after she collected them; hence, she never formally described any herself. However, over the course of her life, she collected more than 150,000 specimens, which would be categorized into two new genera and 500 new species with 50 of those species named after her

An imperfect person

Mexia’s sense of privilege and elitism showed themselves in some of her writings. She wrote disparaging remarks about the indigenous people in the places she collected plants, speaking about the Amazon River where “the wild life and the wilder Indians…lurk in its depths.” She described the other indigenous people, “Rather stunning they were, and quite willing to pose for their pictures in exchange for a few crackers.” Mexia was also known to have a temper, even stabbing the leg of a graduate student at UC Berkeley after the student teased her while having lunch.

Mexia's legacy

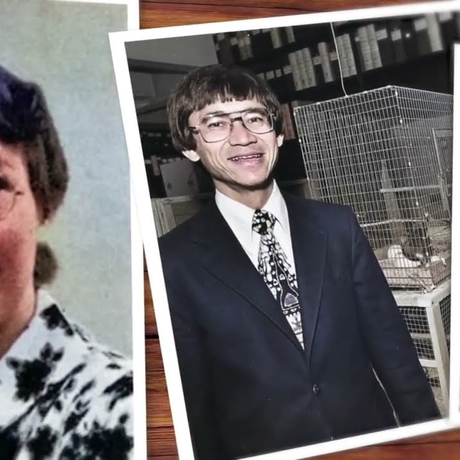

Much of Mexia’s life is known to us because of the work of N. Floy Bracelin, affectionately known as Bracie. Bracie and Mexia became friends in a 1927 University of California field course. Following an expedition to Mexico and South America, in 1928 Bracie began curating the plants Mexia collected on her trips, a partnership that continued even after Mexia’s death in 1938.

In her will, Mexia gave $25,000 to the Sierra Club and $25,000 to the Save the Redwoods League, which purchased Fern Canyon in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park in Mexia’s honor because she especially loved ferns. Mexia’s will also provided for Bracie to continue working at the California Academy of Sciences, curating Mexia’s collections and other plant collections.

Mexia was an adventurous woman who has taught us the power of taking on new challenges with courage. Mexia herself summed up her outlook on plant collecting and life in general when she said, “I don’t think there’s any place in the world where a woman can’t venture alone.

References

Anema, D. 2019. The Perfect Specimen: The 20th Century Renown Botanist Ynés Mexía. Durlynn Anema, 2019.

Bracelin, N. F.. Oct. 1938. “Ynes Mexia.” Madroño IV (8): 273-275.

Bracelin, N. F.. “The Ynes Mexia Botanical Collections,” an oral history conducted 1965 and 1967 by Annetta Carter. Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1982.

Colby, W.E. May 1951. “Mexia Bequest to Sierra Club—Obituary.” Sierra Club Bulletin 36(5): 140–141.

Mexia, Y. 1933. “Three Thousand Miles Up the Amazon.” Sierra Club Bulletin.

Moore, P. A. 1996. Cultivating science in the field: Alice Eastwood, Ynés Mexía and California botany, 1890–1940. PhD dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

“U.C. Scientist Back From Trip Into South America for Plants.” 6 Mar. 1937.

“Ynés Mexía Collections and N. Floy (Mrs. H.P.) Bracelin.” 1975. Notes and News, Madroño 23.

About the author

Katherine Montana is a Library Research Assistant and Graduate Student in the Esposito Lab.

Academy Library and Archives

California Academy of Sciences

55 Music Concourse Drive

San Francisco, CA 94118