This blog post was originally posted at From the Stacks: the Academy Library blog on July 18, 2011

Greetings from the nation’s capital! I have been working on the California Academy of Sciences Connecting Content project as the Information Connections Research Intern, based at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. I have been conducting research for the past six weeks into the information connections between archival scientific field books, digitized scientific publications, and natural history specimen collections. I’d like to introduce the nature of the research I’m doing and report on some of my findings. Field books containing specimen data and observations, publications resulting from formalized post-expedition research, and natural history specimen collection databases comprise an information relationship with multiple points of entry. The connective thread may be followed in any number of directions depending upon how the sources are cross-referenced. For example, a specimen number (“CAS 3156”) in a CAS Collection Database could be searched in JSTOR to see if it has been cited in a publication. Assuming it has been cited, one could proceed to search the collector’s field notebooks, to see if the same specimen is recorded in the field.

Galapagos Penguins. Gerald and Buff Corsi © California Academy of Sciences

Galapagos Penguins. Gerald and Buff Corsi © California Academy of Sciences

I have discovered that beginning with the field book itself, surveying its format and contents for geographical location, dates, and presence of specimen numbers, followed by searching the relevant author or curator in JSTOR or the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) quickly narrows down whether there is a direct link between a scientific publication and an expedition field book. If such a link exists, then searching the relevant natural history specimen collection database for holdings which can be verified as the same specimens described in the original field book is the next step. Of the different types of matches between these sources that arise through this research methodology, the three of greatest interest to the research goals of the project are the direct three-way match, the indirect three-way match, and the ambiguous possible three-way match. A direct three-way match describes an information relationship in which collected specimens are recorded with numbers in a field book, those same numbers, along with the same locations and dates, are cited in a digitized publication, and an institutional specimen collection database includes the same specimens, citing the original field book number.

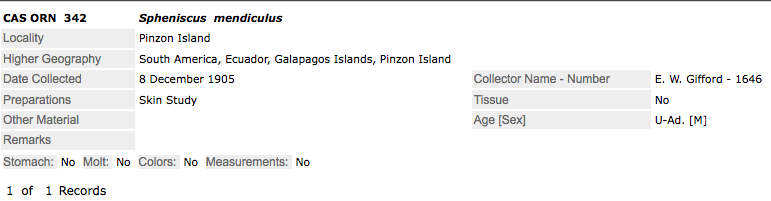

To illustrate how that works, here is a selection from a yet to be digitized field book created by the 1905-06 Galápagos Expedition ornithologist, Gifford: "December 8 1905, Duncan (Pinzon) Island: Spheniscus mendiculus [1646]. I shot one in the forenoon which was swimming and diving about the little cove…". The date, location and a specimen number are given in this primary collecting document. After a search of the BHL, a publication authored by Gifford titled The Birds of the Galapagos Islands describes the following encounter in his section on Spheniscus mendiculus, or Galápagos penguin, as having occurred on December 8 1905:

The specimen number has a prefix CAS, referring to its number in the California Academy of Sciences Ornithology Collections. One of the frequent complications in my information connections research is keeping track of individual collector numbering systems and the numbering systems of the institutions that later accession the specimens. Luckily, the collection databases at times do an excellent job of preserving the original collector specimen number along with its number in the scope of all CAS bird specimens.

Since Giffords' number 1646 is traceable with geographic and location verification from the field book, to a publication, to a collection database, it represents the information relationship I have termed a direct three-way match. As you may guess, things do not often line up quite this nicely, and the indirect three-way matches, ambiguous possible matches, and nil matches are much more frequent occurrences. However, that the life of a collecting event on an expedition over 100 years ago is traceable via modern technological tools is an exciting development in the use of primary sources in the sciences, and as more of these field books are cataloged and digitized this rich connective information will be integrated smoothly into biodiversity research.

- Richard Fischer, Information Connections Research Intern