Our race to discover and describe the unique fauna and flora of São Tomé and Príncipe continues, and the six members of Gulf of Guinea Expedition III (B) are diving in the ancient waters of Príncipe as I write; they return to the Academy next week. As I wrote earlier, Marta is sampling the sea slug fauna (nudibranchs), Gary, Bob and Dana are looking at coral and barnacles, having found a new species of the latter in waters off São Tomé during GG II, and John and David are looking at small marine fish, with emphasis on eels. The group has an added goal, and that is to bring back some freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium) that abound in the São Tomé rivers. These specimens are for a young high school student named Alex Kim.

A freshwater Macrobrachium prawn from Guinea (www.)

Alex is a senior at Thomas Jefferson High School of Science and Technology in Virginia. He is doing an ambitious biogeography project on these prawns, relatives of which are found on both sides of the Atlantic. Alex contacted me through this blog—you can read his comments at the end the November posting. During a brief visit to DC over the holidays, I brought some preserved specimens we collected in GG I and GG II which I handed over to one of his advisors, Dr. Patrick Gillevet of George Mason University, and now the GG III (B) group plans to bring him some fresh material for DNA studies. This is really fun academic stuff, and we are delighted to have the involvement of a young colleague.

A Macrobrachium prawn from Cameroon. (www)

Except for documenting our exciting hunt for Príncipe Jita, (see first May posting), I have not written that much about the endemic reptiles of these islands; in fact, there are quite a few of them, some rather spectacular. While reptiles, especially geckos and skinks, are much better dispersers over saltwater than amphibians, snakes are not particularly good at it; moreover, like the amphibian caecilian, cobra bobo, a number of these endemics are legless species. There are also some island species that may be endemic, but we are not sure…. we just haven’t studied them closely enough yet. In this posting I will show you the unique lizard species. One readily identifiable endemic species is Greeff’s gecko, or the Giant gecko, Hemidactylus greeffii.

[

[

Greeff's Gecko, Hemidactylus greeffii . A Sao Tome specimen. RCD phot. GG I

Greeff’s gecko is an island giant; it is evidently much larger than other African member of the genus (and there are over 55 African taxa of Hemidactylus with likely many more to be discovered). Our longest specimen is over 200 mm in total length (including original tail); but longer specimens are known. This gecko is not only very large it also differs from all of its African relatives in lacking a claw on the first (inner) finger and first toe. Somehow, this feature has been lost during the thousands, perhaps millions of years of isolation on the Gulf of Guinea Islands. Greeff’s gecko also has greenish eyes, which also distinguishes it from other nocturnal geckos on the island which, so far as we know, are not endemics.

H. greeffii. Note absence of claw on first thumb. ST specimen. RCD phot. GGI

H. greeffii with greenish eyes. ST specimen. D. Lin phot. GG II.

Greeff’s gecko occurs on both São Tomé and Príncipe; at least we think it does. Here’s what I mean: specimens from both islands look very much the same but a couple of years ago, a group of researchers from the University of Madeira and Portugal looked at the DNA of specimens from both islands and found that data from mitochondrial DNA suggested the two populations were very different, and that they may well be two distinct species in spite of their apparent anatomical similarity. These results were not confirmed by study of nuclear DNA however, so scientifically the “jury” is still out, and we call both island forms, Greeff’s gecko. This critter is quite common in rock walls, culverts, rock crevices on both islands and is strictly nocturnal.

Principe specimen of Greeff's gecko. D. Lin phot. GG II.

A similar situation exists with a small terrestrial skink called Panaspis africana, or Gulf Leaf-litter skink. A daytime forager, this small uniform-brown skink is very common in the lowlands; it can be easily heard and seen scuttling through dried cacao leaves and it is almost always found on the ground on both islands; one of our largest gravid (with eggs) female specimens from São Tomé is about 100 mm in total length, but most of our examples are smaller.

Gulf Leaf-litter skink. Panaspis africana; D. Lin phot. GG II.

The same group of researchers from the University of Madeira studied the DNA of leaf litter skinks of both islands, and also Annobón, the last island in the chain and part of Equatorial Guinea. They used, in part, tissues and specimens collected by us during GG I in 2001. In this case they found clear evidence for three separate species, one on each island (the one on Annobón is already called P. annobonensis); this was supported by both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence. However, in one of those tragic, fortunately rare, occurrences in science, the specimens from which the tissue samples were taken were either lost in transit or misplaced. Without voucher samples the results cannot be duplicated or tested nor can we demonstrate the results. So for now, although there was evidence that Panaspis is two different species on São Tomé and Príncipe we cannot confidently describe the populations of the different islands nor give them scientific names. Until the study can be redone with new material, the Gulf leaf-litter skinks remain known as simply Panaspis africana.

Author working on Principe. Weckerphoto. GGIII

The way we collect these specimens is not sophisticated – we use our hands. We turn over logs, rocks and branches on the ground or sift through leaf litter with rakes; we climb trees and cliffs; we go out at night with flashlights and headlamps. After capture, the specimens are put in separate plastic bags for later processing.

Dr. Iwamoto in Sao Tome H. greeffii habitat on Sao Tome. RCD phot. GG I

Jens Vindum searching leaf litter on Sao Tome. D. Lin phot. GG II

Principe day gecko in plasic bag. RDC phot. GG III.

Every specimen we collect gets a unique field number, which is the same used for photographs of it, recordings or tissues samples taken.

My grad student, Ricka Stoelting, processing specimens on Principe. RCD phot. GG I

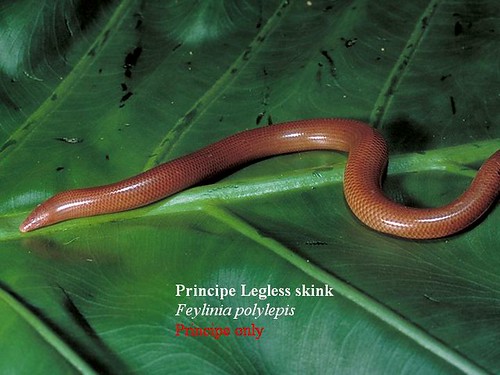

Certainly one of the oddest endemic lizards is the legless skink, unique to Príncipe Island, Feylinia polylepis. There are about six species known in this genus, the remaining five found broadly distributed on the African mainland.

Principe legless skink, Feylinia polylepis. brown phase. D. Lin phot. GG I.

They appear in two different color morphs, a brown one and a pale gray one, regardless of size or sex. The locals call them, Ozhgah (or at least the name sounds like that).

Principe legless skin - grey phase. D. Lin phot. GG II

Feylinia polylepis head shot. D. Lin phot. GG II

They can be found under almost anything on the ground provided the earth is slightly moist. Once exposed, they are very quick and can rapidly disappear into holes in the ground. They are conspicuously common in the Príncipe lowlands, and in this regard are reminiscent of the caecilians of São Tomé Island; the high density of their numbers in suitable habitats suggests predation may be low in these areas.

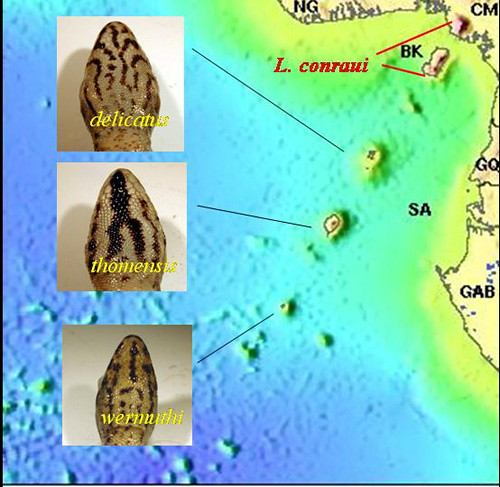

Not all geckos are nocturnal. In the Old World there are two large groups that are secondarily diurnal, although they, like all geckos, lack eyelids. The genus Phelsuma is a group of numerous species of velvety green geckos found on Madagascar and the Indian Ocean islands; the other group, Lygodactylus are also present in Madagascar but also distributed throughout the Afrotropical region as well. They are not brightly colored, and taxonomically rather poorly known. The group as a whole is being studied by Dr. David Vieites (and his students) of Madrid and Dr. Adam Leache, of the University of Washington. I have been involved as well but largely in studying the relationships of day geckos of the Gulf of Guinea Islands.

Lygodactylus thomensis. Sao Tome. D. Lin phot. GGI

The Gulf of Guinea Day geckos are sun-lovers and strictly climbers, being fairly common on tree trunks and scuttling up walls even in São Tomé town and Santo Antonio, Príncipe. They are very small, at about 70-80 mm total length. The day geckos of the Gulf of Guinea islands (excluding the continental island of Bioko) have long been recognized as a distinct, endemic species, Lygodactylus thomensis, first discovered on São Tomé Island. The day geckos on Príncipe and Annobón have been described as subspecies (or races, if you will) of the São Tomé species.. As you can see from the illustration below, one of the characteristics used to define species of day geckos is the throat pattern.

Day geckos of the Gulf of Guinea Islands. RCD prep.

The throat patterns of the lizards on each of the three islands are quite consistently distinct from one another, and work by us and the University of Madeira suggest that they have been isolated from each other for a long, long time, and that each is a full species unique to its island. Work is continuing on these lizards.

L. delicatus of Príncipe Island. RCD phot. GG III

There are other conspicuous lizards on both islands but these are not considered endemics; i.e., they occur elsewhere and are probably just good over-water dispersers. The large speckled-lipped skink, Mabuya maculilabris, is common and widespread in the lowlands of both São Tomé and Príncipe. It is a good climber and is seen in a variety of habitats especially along the coast lines. This species also broadly distributed on the African mainland.

Speckle-lipped skink (Mabuya maculilabris) of the Gulf of Guinea. Sao Tome. D. Lin phot. GG II]

M. maculilabris detail. D. Lin phot. GGII

There are also non-endemic, nocturnal geckos on both islands. Most appear to be the widespread house gecko, Hemidactylus mabouia, also occuring nearly throughout Africa.

House gecko, Hemidactylus mabouia. D. Lin. phot. GG II\]

Note that the eyes are not greenish and that this species does not lack claws on the inner toe and finger. There is some confusion as to how many non-endemic species are present and what to call them.

H. mabouia foot from below. note claws. Weckerphoto, GG III

Snakes are coming next.

Here’s the parting shot:

The thrill of discovery! Bom Bom Island, Principe. Weckerphoto. GG III

PARTNERS We gratefully acknowledge the support of the G. Lindsay Field Research Fund, Hagey Research Venture Fund of the California Academy of Sciences, the Société de Conservation et Développement (SCD) for logistics, ground transportation and lodging, STePUP of Sao Tome http://www.stepup.st/, Arlindo de Ceita Carvalho, Director General, Victor Bomfim, Salvador Sousa Pontes and Danilo Bardero of the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Sao Tome and Principe for permission to export specimens for study, and the continued support of Bastien Loloumb of Monte Pico and Faustino Oliviera, Director of the botanical garden at Bom Sucesso. Special thanks for the generosity of private individuals, George F. Breed, Gerry F. Ohrstrom, Timothy M. Muller, Mrs. W. H. V. Brooke and Mr. and Mrs. Michael Murkami for helping make these expeditions possible.