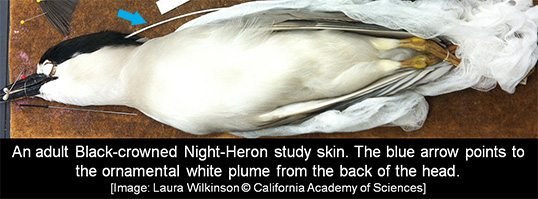

This week, I prepared a study skin of a wetland bird called a Black-crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), the most widespread heron species in the world. There are 64 species in the heron family (Ardeidae), which also includes egrets and bitterns. Black-crowned Night-Herons forage for fish, amphibians, insects, and other types of food during the evening, avoiding competition with the other heron species that use the same wetlands during the day. Night-Herons nest in colonies with other heron and egret species in trees or other vegetation, usually over water. Adults and juveniles look drastically different, with adults sporting long white ornamental plumes on their heads.

These birds, like most bird species, will raise any chick in its nest, meaning that they are unable to distinguish between their own biological offspring and those of other parents. In a previous blog, Codie talked about brood parasitism, which occurs when a bird lays its eggs in another bird’s nest, leaving that parent to raise offspring that aren’t biologically theirs. This can be done by more species than the commonly known Cowbirds and Cuckoos! By not being able to distinguish between chicks in their nest, Night-Herons can become victim to this kind of brood parasitism, and have been documented to be parasitized by Black-headed ducks. There is, however, another kind of brood parasitism called “conspecific brood parasitism.” This strategy is when a bird lays its eggs in the nest of a bird of the same species. This occurs in another marsh bird species, the American Coot (Fulica Americana), which has a high rate of conspecific brood parasitism. Females will lay their eggs in other females’ nests, potentially increasing their own reproductive success. Unlike Night-Herons, however, Coots have developed strategies to recognize their own young and reject the young of competing parents.

The strategies that different species evolve to make them as biologically successful as possible are fascinating, from brood parasitism to elaborate dances and plumages, and can be seen in all types of birds. If you’re interested in seeing Black-crowned Night-Herons in San Francisco, you can find them year-round in different wetland areas such as the lakes in Golden Gate Park as well as harbors and piers.

Laura Wilkinson

Curatorial Assistant & Specimen Preparator

Ornithology & Mammalogy