Most weeks I write about my research subjects: nudibranchs. This week I thought I’d learn something new and write about some shelled marine snails.

One of the highlights of my trip to Papua New Guinea last year was finding the largest live snail that I’ve ever seen in my life. I found the snail on a night dive while looking for nudibranchs. As I approached a large structure, a coral head or perhaps it was a coral-covered boulder, I remember seeing a snail nearly the size of a football. It was brown in color and its foot was spread out from under its shell like a thick carpet as it moved up the side of the structure. I remember being overwhelmed with excitement having come across such a large snail, especially as I was looking over sand grains in search of slugs the length of grains of rice! I immediately decided to collect this live snail, since I couldn’t recall anyone collecting anything quite like this yet on our biodiversity survey. I grabbed it by the shell and placed it in my catch bag. It took up a majority of the space in the bag and added a fair amount of weight!

While diving in in the field, our team had an in-house competition on each dive to see who could find the most interesting or beautiful specimen, clearly this time, I had won the “shell of the show.” When we returned to the lab, everyone was excited to see such a large snail, and I was told that it was a member of the group commonly called “bailer” snails. Our shelled snail experts identified this particular species as Melo broderipii.

Melo is a genus of snails that belongs to the family Volutidae. Many volutes have large shells and some of the largest shells in this family can be found within the genus Melo. Some of the shells of certain species can grow to 50 cm (19.7 in) in length! The common name “bailer” comes from the shape of the shell, which can be used to “bail” out water from boats or canoes. Members of this group are carnivores and eat other snails and seem to live primarily on a muddy or sandy bottom. They appear to bury themselves during the day and are active at night.

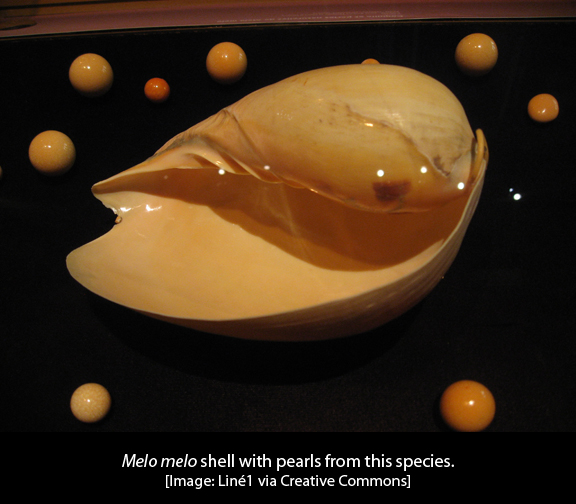

An interesting thing I read about Melo snails is that they are capable of producing pearls. Unlike the pearls that are found in oysters, these pearls are not iridescent because they do not contain nacre, which is what makes other pearls and parts of shells iridescent. Instead, these pearls are yellow to orange in color and have a sort of “flame” pattern to them. To me, they look very much like marbles!

These animals are eaten by humans and the shells sold for a variety of uses. Apparently, they are sometimes used as horns in ceremonies or as ashtrays.

I never cease to be amazed by the diversity of organisms that live on our planet. I think I might delve into these snails a bit more...

Until next time!

Vanessa Knutson

Project Lab Coordinator

Sources:

http://www.palagems.com/melo_myanmar.htm

http://www.sea-ex.com/fishphotos/baler-shell-commercial-fishery.htm