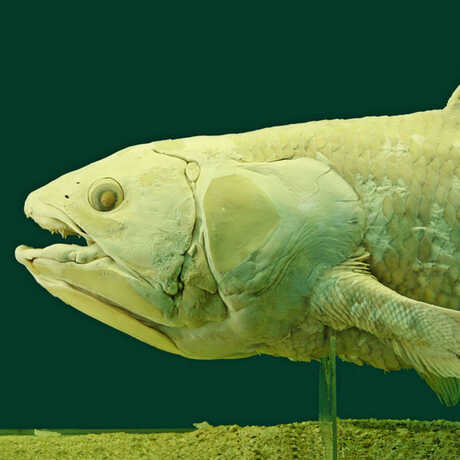

In 1938, when a fisherman off the coast of Africa inadvertently caught a coelacanth, it was heralded as the biological find of the century. Thought to be the missing link between amphibians and fish, coelacanths are big, oily, strange-looking fish that grow up to six feet in length and weigh 200 pounds. According to the fossil record, the coelacanth was thought to have gone extinct eighty million years ago. John McCosker, Chair of Aquatic Biology, says, “It was like finding a living T. rex.”

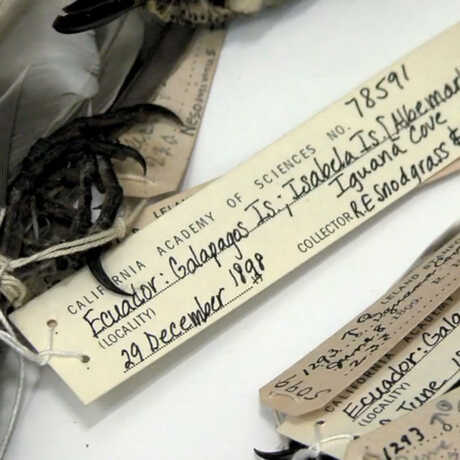

In 1975, the California Academy of Sciences sent McCosker and a team of oceanographers to Grand Comore, an island in the Indian Ocean off the eastern coast of Africa. McCosker's mission: to learn as much as possible about the coelacanth. Despite accidentally wandering into the midst of an insurrection against French colonialists, McCosker still managed to obtain two frozen coelacanths. The coelacanths were also preserved on 50 franc stamps issued by the Comoro Islands.

Packing his specimens in dry ice, McCosker made his way back to the states, where he sold one specimen to his alma mater—the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, based in La Jolla, CA. That sale helped to pay for the expedition, enabling McCosker to dissect the remaining coelacanth. Both specimens provided researchers at numerous laboratories with an unparalleled opportunity to perform dissections, examine tissue, and determine if coelacanths were, in fact, the missing link between fish and amphibians.

Unfortunately for the coelacanth, that special designation was not to be. “It was once thought that the coelacanth walked out of the water on its bony limb-like fins and became an amphibian,” says McCosker. “That designation now goes to the lungfish.” Today, the coelacanth is regarded as a still-living remnant of an ancient evolutionary line. However, McCosker notes with satisfaction, the coelacanth survives in the popular imagination as a form of insult in politics, where it is a term used to describe politicians too old, fossilized, and set in their ways to change.