We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

A Closer Look at Exoplanets

May 21, 2014

by Jami Smith

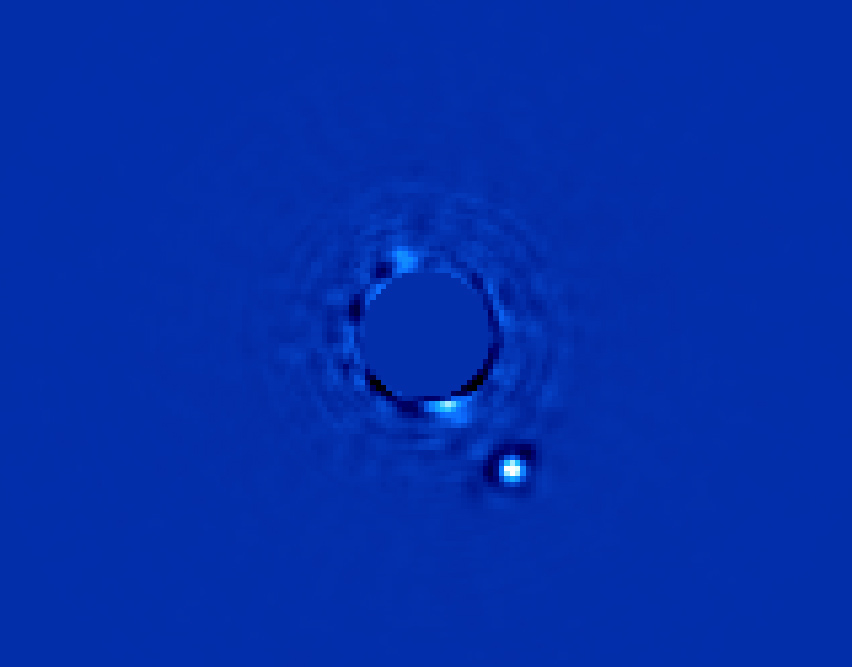

A new instrument installed at the Gemini South telescope in Chile has captured the best-ever direct image of a planet outside our solar system.

The Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) took nearly a decade in development and testing, but the payoff occurred almost immediately! In its first observations, the GPI produced an impressive image of Beta Pictoris b, a planet approximately 63 light-years away. The GPI made the image with just a 60-second exposure; earlier instruments would have required more than an hour.

“We finally got it operational on the telescope last November, and it worked beautifully right out of the box,” says Bruce Macintosh, a Stanford professor of physics and principal investigator for the GPI system. “Even these early first-light images are almost a factor of 10 better than the previous generation of instruments.”

Morrison Planetarium’s Director wrote about GPI back in January, but a lot has happened since then, as the project finishes its roll-out period… You can read about the process on the GPI blog, giving you a scientist’s perspective on the challenges of commissioning a complex astronomical instrument.

The GPI detects infrared radiation from young planets that trace wide orbits around their stars—planets we believe are similar to the giants in our own solar system not long after their formation. Young planets such as Beta Pictoris b are easier to spot than older planets because they are still radiating heat from their formations. The imager was built to find the radiation of those new exoplanets while masking out the bright starlight of their parent stars. Blinding starlight has caused problems for earlier instruments searching for exoplanets.

“Most planets that we know about to date are only known because of indirect methods that tell us a planet is there, a bit about its orbit and mass, but not much else,” says Macintosh. “With GPI, we directly image planets around stars – it’s a bit like being able to dissect the system and really dive into the planet’s atmospheric makeup and characteristics.”

There are limitations. Earth’s atmosphere is turbulent and visually noisy, so even with this advanced technology, the ground-based GPI will only be able to view bigger exoplanets, those about the size of Jupiter. But the technology is being proposed for use on future space-based telescopes.

“Someday there will be an instrument that will look a lot like GPI on a telescope in space,” Macintosh predicts. “And the images and spectra that will come out of that instrument will show a little blue dot that is another Earth.”

This year the GPI team plans to survey 600 young stars and their orbiting planets. “Seeing a planet close to a star after just one minute was a thrill, and we saw this on only the first week after the instrument was put on the telescope,” says Fredrik Rantakyro, instrument scientist for GPI. “Imagine what it will be able to do once we tweak and completely tune its performance.”

More details about the GPI can be found in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Image: Processing by Christian Marois, NRC Canada.