Special delivery! See our visiting baby yaks (Dec. 20–Jan. 5) this holiday. Learn more

Science News

Climate and Ocean Currents

April 26, 2010

Imagine an ocean current three miles deep and 31 miles wide that travels over 2000 feet per hour and carries more than 12 million cubic meters a second of very cold water from Antarctica.

Scientists from Japan and Australia have confirmed the size and speed of such a current in an article published online yesterday in Nature Geoscience.

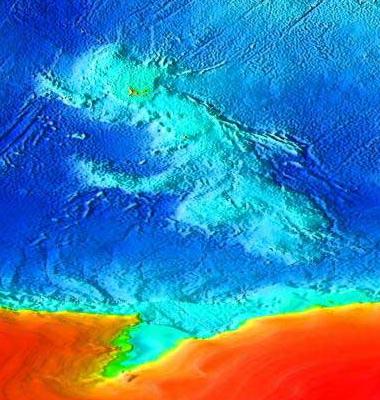

The current moves northwest from the eastern edge of the Kerguelen Plateau (pictured in light blue above an orange Antarctica here), in the southern Indian Ocean.

"The deep current along the Kerguelen Plateau is part of a global system of ocean currents called the overturning circulation, which determines how much heat and carbon the ocean can soak up," one of the paper’s authors, Steve Rintoul, said.

These currents are sometimes called the oceans’ conveyor belt, combining all of the Earth’s oceans into a global system. Another one of these currents is the Gulf Stream that brings warmer water to Northern Europe, keeping its climate mild. It is also the reason for the upwelling that occurs across the world and especially in our own backyard—the North Pacific Ocean.

These currents have sometimes been known to change. "We're not saying this could happen instantaneously, like the movie The Day After Tomorrow," lead author Yasushi Fukamachi, an ocean scientist at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan says. "But understanding this kind of current is very important to understanding global climate."

Alejandro Orsi, a physical oceanographer at Texas A & M University in College Station agrees. According to an article in Nature, he says, “This (current) is significant because it represents a ‘fast lane’ by which climatic and environmental changes affecting the Southern Ocean can propagate northward. Proof that this is already occurring can be seen from the fact that the deep waters near the Kerguelen Plateau already show ‘clear signs’ of reduced salinity relating to changes in the rate of melting of Antarctic ice sheets.”

In other words, by following this large current, scientists hope to follow the affects of climate change.