We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

Food Webs Before the Impact

October 30, 2012

What killed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago? Were they declining before some mass extinction event or did they just go kablooie?

This isn’t just a question heard on the playground; it’s asked by scientists as well. Though many agree that the mountain-sized asteroid (that left the now-buried Chicxulub impact crater on the coast of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula) ultimately caused the mass extinction, some scientists continue to argue about the health of dinosaurs before the event.

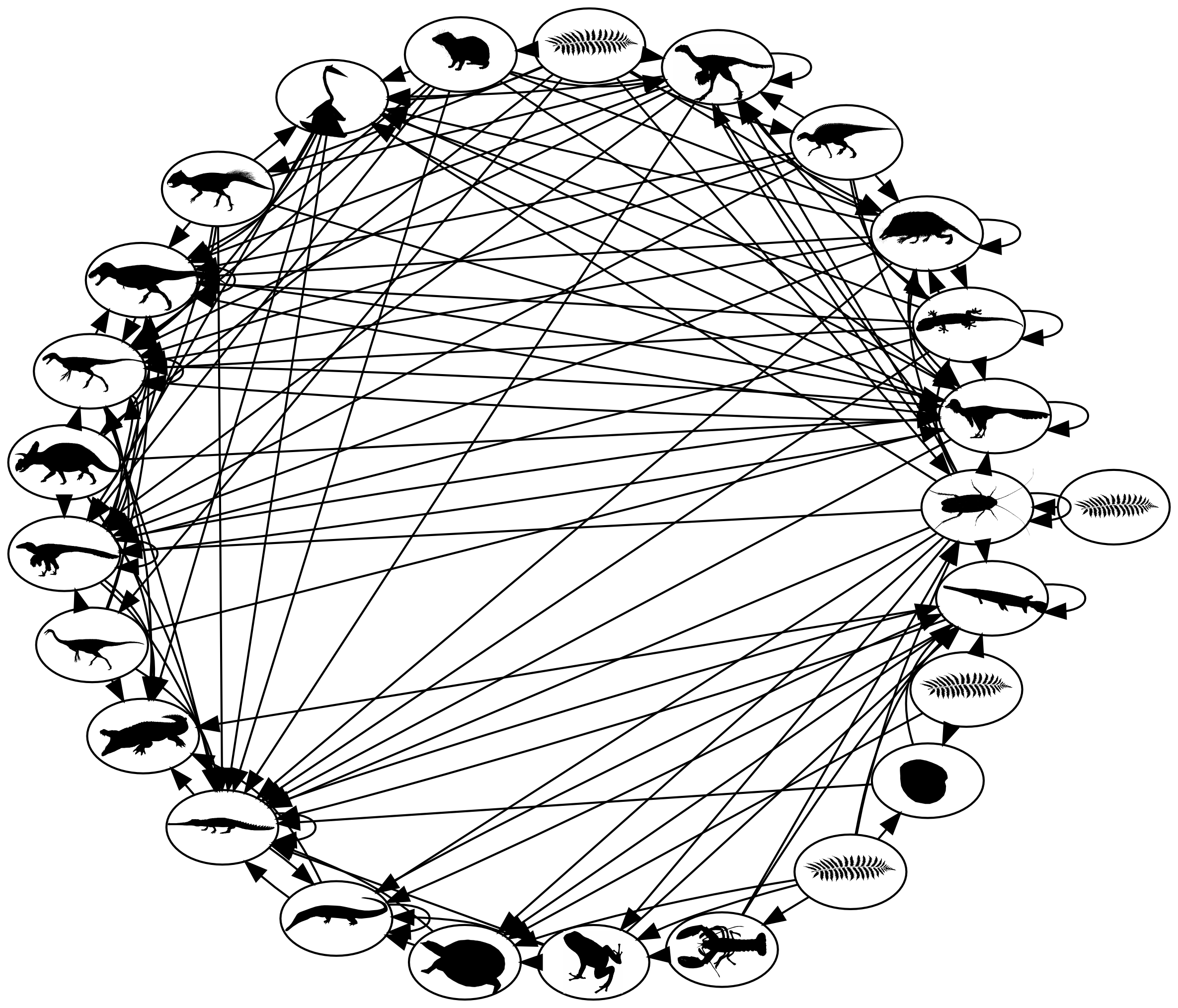

A new study this week, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences looks at the health of ecosystems from 13 million to 2 million years prior to the impact. The Academy's Peter Roopnarine and his colleagues constructed food webs to examine the communities that lived in North America at the time.

In fact, Peter has spent the past eight years constructing paleo food webs, looking comprehensively at who lived in a particular place at a particular time, what they ate and who ate them. It’s a great way to see into the past.

Constructing these food webs involves looking at the fossil record—bone damage, stomach contents, etc.—and creating computer models. Peter says this involves a lot of data. He finds ecologically similar species that occupied a similar space and time and likely shared the same predators and prey. He starts by creating links between them and then builds from there.

Peter also looks at the present to reconstruct the past. He looks at how predators and prey are distributed in a modern ecosystem—there will only be so many top predators, for example, yet there will be many organisms at the bottom of the food web. Peter says that modern food webs are dominated by specialists—those that just eat a few organisms. But as you follow along, you’ll find a few generalists that consume an assortment of items.

Like a baseball statistician looking to build a new team, Peter uses these numbers and statistics from current players to input into his model to map past scenarios.

But, of course, the food web he models represents just one possibility of how that ecosystem looked at that time. So Peter runs the model thousands of times to get the average picture of the dynamics of the food web.

Now back to the dinosaurs… Running the food webs for 13 million years before the impact, Peter and his colleagues found that the ecosystems had been changing in North America. There was less diversity of species with lots of smaller vertebrates and very, very large herbivores. These changes could have taken place when the interior western seaway dried up, which would have affected climate and vegetation.

This doesn't mean that the ecosystems were fragile by any means. Peter says. They were fine, robust even. Perhaps just a little less robust closer to the impact.

But when the impact hit, these small differences played a significant role, Peter explains. The ecosystems were a bit more vulnerable. “It was a bad time to be alive.”

“Our study suggests that the severity of the mass extinction in North America was greater because of the ecological structure of communities at the time,” notes Peter’s colleague and lead author of the paper Jonathan Mitchell of the University of Chicago.

And these small changes in the past can help us learn what might happen in future major events, says Peter. “What do extreme occurrences look like, where is our vulnerability, what does a recovery look like? Besides shedding light on this ancient extinction, our findings imply that seemingly innocuous changes to ecosystems caused by humans might reduce the ecosystems’ abilities to withstand unexpected disturbances.”