We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

Hot or Not?

June 27, 2011

by Anne Holden

Scientists’ vision of dinosaurs has changed a lot since they were first described in 1842. Gone are the slow, lumbering depictions popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Over the last few decades, those images have quickly been replaced by those of the quick, agile Tyrannosaurus Rex and Velociraptor depicted Jurassic Park.

But was this speed and agility accompanied by warm body temperatures? The question as to the relative warm-bloodedness of dinosaurs has been hotly debated among paleontologists. Now, a new study from scientists at the California Institute of Technology for the first time has directly analyzed dinosaur remains. Their goal? To calculate the body temperatures of some of the largest dinosaurs that ever walked the planet. The study is reported in the June 23 issue of Science Express.

The traditional view on dinosaurs’ body temperatures has been that similarities to modern-day cold-blooded reptiles imply that they, too, were cold-blooded. Reptiles like crocodiles, snakes, and lizards can’t maintain an internal body temperature and are classified as cold-blooded, or exothermic. By contrast, warm-blooded, or endothermic, animals can. Birds and mammals – including us humans – are endotherms.

Some paleontologists have argued that physical movements and behavior of dinosaurs – how they tracked prey, where they lived – implied that they must have been endothermic. But the indirect methods used in making these claims have been debated as scientists were unable to directly measure the body temperature of fossilized dinosaurs.

That is, until Robert Eagle and his team at Cal Tech figured out a way to do just that. “The consensus was that no one would ever measure dinosaur body temperature, that it’s impossible to do,” says John Eiler, a professor of geology and geochemistry at Cal Tech and one of the study’s co-authors. But the team found the key to doing so lie in the dinosaurs’ teeth.

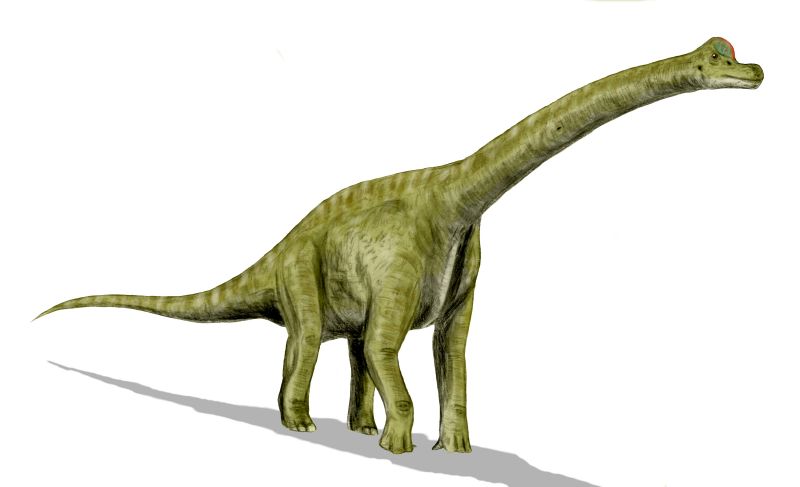

Using a cutting-edge technique called clumping isotope analysis, the team examined 11 dinosaur teeth excavated from sites in Africa and North America. These teeth belonged to several large dinosaur species, including Brachiosaurus and Camarasaurus. Within each tooth, the researchers measured levels of two rare elements, carbon-13 and oxygen-18. Sometimes these elements (also known as isotopes) are found ‘clumped’ together in the tooth enamel. According to the team, how often these isotopes clump together depends on the body temperature of the individual. The lower the temperature, the more they clump.

When they tested the fossilized teeth, the team calculated a body temperature of about 38.2⁰C (100⁰F) in the Brachiosaurus, and about 35.7⁰C in the Camarasaurus (96.3⁰F). Strikingly similar to body temperatures in many mammals, and much warmer than their reptilian counterparts.

But warmer body temperatures don’t necessarily equal a warm-blooded animal, say the authors. Brachiasaurs could weigh more than 43 metric tons. As Eiler explains, “If you’re an animal that you can approximate as a sphere of meat the size of a room, you can’t be cold unless you’re dead.” According to Eiler, even a large exothermic animal would have a warmer body temperature than a small one.

Eagle and his team maintain, therefore, that dinosaurs were neither endotherms nor exotherms. Rather, dinosaurs were gigantotherms: they maintained warm body temperatures simply due to their size.

But what about smaller dinosaurs? Would species like Procompsognathus, which stood less than 4 feet high, have a similar metabolism and body temperature as the 50 feet tall Brachiosaurus? Answering these and other questions is next on the researchers’ radar, as understanding the body temperatures of dinosaurs of all sizes could give clues to how they evolved hundreds of millions of years ago.

Anne Holden, a docent at the California Academy of Sciences, is a PhD trained genetic anthropologist and science writer living in San Francisco.

Image by Nobu Tamura/Wikimedia