Please note: Osher Rainforest will be closed for maintenance Jan. 14–16.

Science News

Mammal Size

November 29, 2010

Felisa Smith was a graduate student at UC Irvine in the 1980s when she became obsessed with mammal size. "I worked on a number of islands off the coast of Baja, California where rodents had evolved into gigantic body sizes. I've been interested in size ever since."

Her latest study is three years in the making and a collaboration with a team of paleontologists, evolutionary biologists and macroecologists from universities around the world. The team studied the growth of mammal size after the dinosaurs went extinct around 65 million years ago and published their results last week in the journal Science.

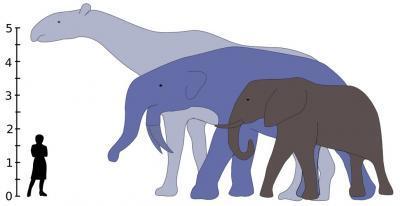

Smith and her colleagues found that mammals grew from a maximum of about 10 kilograms (22 pounds) when they shared the Earth with dinosaurs to a maximum of 17 tons afterwards. They found that this pattern was surprisingly consistent globally and across time and trophic groups and lineages—that is, animals with differing diets and/or descended from different ancestors.

From the Observations blog in Scientific American:

But across all of the major continents, during the first 25 million years after the dinosaurs were wiped out, mammals underwent an explosive growth spurt. By 42 million years ago, however, the researchers found, the intense growth had leveled off.

What was the peak of land mammal growth? Indricotherium transouralicum was the largest mammal that ever walked the Earth. It was a hornless rhinoceros-like herbivore that weighed approximately 17 tons, stood about 18 feet high at the shoulder and lived almost 34 million years ago.

The overall results give clues as to what sets the limits on maximum body size on land -- the amount of space available to each animal and the climate they live in. The colder the climate, the bigger the mammals seem to get, as bigger animals conserve heat better. The results also show that no one group of mammals dominates the largest size class.

Size does matter, says Smith, "Understanding the constraints operating on size is crucial to understanding how ecosystems work."

Image: Alison Boyer/Yale University