We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

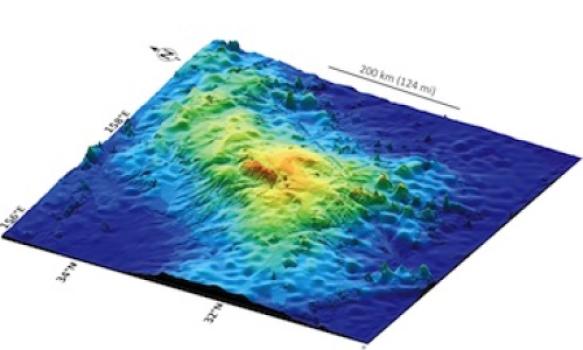

Massive Tamu Massif

September 9, 2013

by Molly Michelson

How can you hide a large volcano here on Earth? Place it several miles below the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

Researchers, reporting this week in Nature Geoscience, have discovered just that: a hidden volcano so big it can rival some of the largest in the Solar System. (Think Olympic Mons on Mars.) For several million years, Tamu Massif, has been under cover in the northwest Pacific Ocean, about 1,000 miles east of Japan where three tectonic plates meet: the Pacific, the Farallon and the Izanagi.

Scientists knew there were underwater volcanoes in the Shatsky Rise but it was unclear whether Tamu Massif was a single volcano, or a composite of many eruption points. By integrating several sources of evidence, including core samples and data collected on board the JOIDES Resolution research ship, the authors have confirmed that the mass of basalt that constitutes Tamu Massif did indeed erupt from a single source near the center.

Tamu Massif stands out among underwater volcanoes not just for its size, but also its shape. It is low and broad, meaning that the erupted lava flows must have traveled long distances compared to most other volcanoes on Earth.

Although it rivals Olympic Mons in width and sheer area (about 120,000 square miles), it only rises about 13,000 feet above the sea floor. (Mons is about 14 miles tall! You can thank low martian gravity for that.) Tamu Massif’s tallest point rests at about 6,500 feet below the ocean surface.

“It’s not high, but very wide, so the flank slopes are very gradual,” says lead author William Sager, of the University of Houston. “In fact, if you were standing on its flank, you would have trouble telling which way is downhill. We know that it is a single immense volcano constructed from massive lava flows that emanated from the center of the volcano to form a broad, shield-like shape.”

Thankfully, the massive Tamu Massif is an inactive volcano. Sager and his team put the megavolcano at about 145 million years old, and believe it became inactive within a few million years after it was formed.

“Its shape is different from any other sub-marine volcano found on Earth, and it’s very possible it can give us some clues about how massive volcanoes can form,” Sager says. “An immense amount of magma came from the center, and this magma had to have come from the Earth’s mantle. So this is important information for geologists trying to understand how the Earth’s interior works.”

Image: Will Sager