Please note: Osher Rainforest will be closed for maintenance Jan. 14–16.

Science News

Mouse Memories

July 29, 2013

by Molly Michelson

Memories are unreliable, at least for humans.

According to MIT scientist (and Nobel Prize winner) Susumu Tonegawa, as quoted in Scientific American, only humans have false memories.

“Humans are the most amazing, imaginative animals,” he said. “We are thinking. Lots of things are going on. Humans are recording what happens and passing it on.”

An imperfect memory, Tonegawa said, may be the price we pay for the imagination and creativity that makes us human.

The phenomenon of humans’ false memory is well-documented—in many court cases, defendants have been found guilty on testimony from witnesses and victims who were sure of their recollections, but DNA evidence later overturned the conviction.

But now, Tonegawa and his colleagues have succeeded in also creating false memories in mice, hoping to further understand where and how these fake memories are made in the human brain.

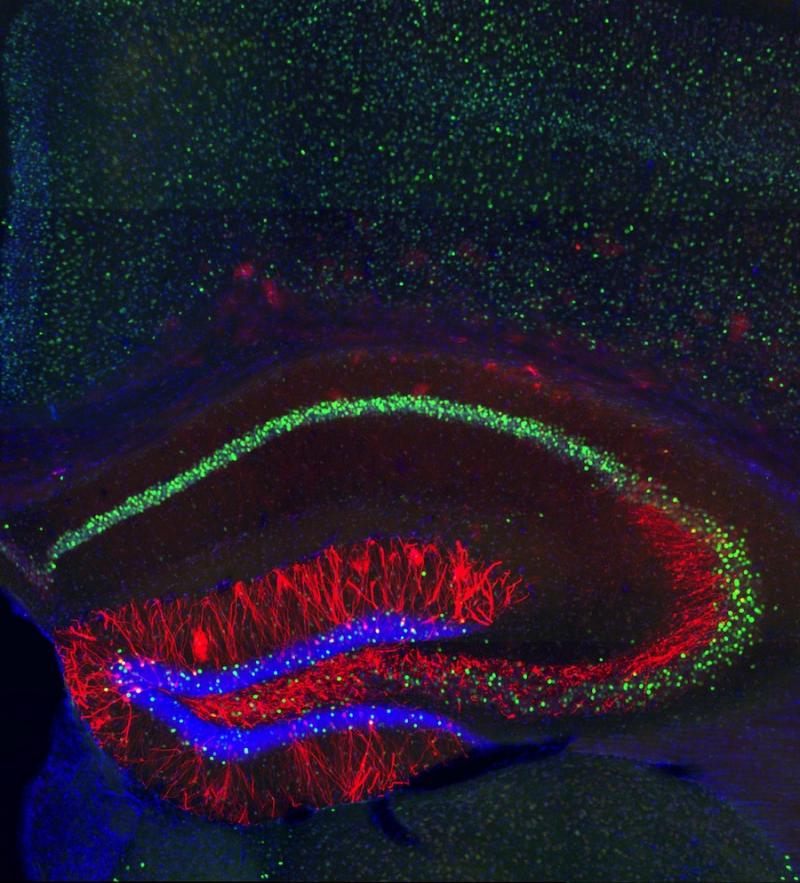

Memories are stored in networks of neurons that form memory traces for each experience we have. Scientists call these traces engrams, and can identify the cells that make up part of an engram for a specific memory and reactivate it with a technology called optogenetics.

Using optogenetics, Tonegawa’s research team started the experiment by putting mice in a chamber and recording their memories of that chamber. The chamber was harmless and pleasant enough that the mice felt comfortable exploring the space. The next day, the researchers moved the mice into a different chamber, stimulating the memory of the previous chamber. The scientists also lightly shocked the rodents’ feet.

On the third day, the mice were placed back into the first chamber. They now froze in fear, even though they had never been shocked there. A false memory had been incepted—the mice feared the memory of the first chamber because when the shock was given in the second, they were reliving the memory of being in the first.

The team discovered they could both implant false memories and that the neurological traces of these false memories are identical in nature to those of authentic memories. “Whether it’s a false or genuine memory, the brain’s neural mechanism underlying the recall of the memory is the same,” says Tonegawa.

The MIT team is now planning further studies of how memories can be distorted in the brain.

The study is published in the current edition of Science.

Image: Steve Ramirez and Xu Liu