We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

New Maya Calendar Find

May 15, 2012

Last week, researchers again confirmed that the world will not end this year.

Some say that ancient Maya calendars end on December 21, 2012, predicting the end of the world as we know it. Scientists have refuted this notion for years, but some refuse to listen.

A new, surprising Maya ruins finding, published last week in Science, again confirms that the end of the world is not nigh.

The authors of the paper say that despite popular belief, the Maya calendar does not end in the year 2012 but simply starts another of its calendar cycles. “It’s like the odometer of a car, with the Maya calendar rolling over from the 120,000s to 130,000,” says Anthony Aveni, professor of astronomy and anthropology at Colgate University, and a co-author of the new paper. “The Maya just start over.”

“The ancient Maya predicted the world would continue, that 7,000 years from now, things would be exactly like this,” lead author William Saturno confirms. “We keep looking for endings. The Maya were looking for a guarantee that nothing would change. It’s an entirely different mindset.”

The ruins in the new paper were discovered in Xultún in Guatemala’s rainforest-covered Petén region. Researchers uncovered a structure that contains what appears to be a work space for the town’s scribe, its walls adorned with unique paintings—one depicting a lineup of men in black uniforms—and hundreds of scrawled numbers. Many numbers involve calculations related to the Maya calendar.

The amazing thing is that this structure is from the 9th Century, making it hundreds of years older than previously discovered (but similarly non-apocalypse predicting) Maya calendars.

Even the structure’s discovery is remarkable—looters have ravaged the surrounding region, and by all accounts, the paintings shouldn’t have lasted these 1,200 years. “It’s weird that the Xultún finds exist at all,” Saturno says. “Such writings and artwork on walls don’t preserve well in the Maya lowlands, especially in a house buried only a meter below the surface.”

(Discover’s 80beats blog has a great illustration of the house-like structure.)

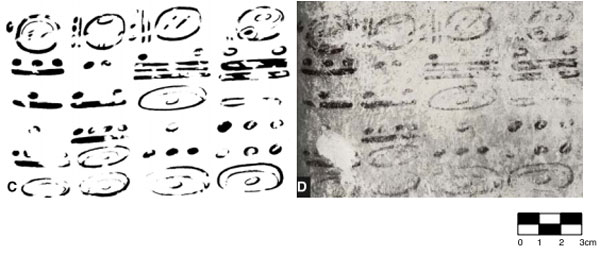

The mural also represents the first Maya art found on the walls of a house. “There are tiny glyphs all over the wall, bars and dots representing columns of numbers. It’s the kind of thing that only appears in one place—the Dresden Codex—which the Maya wrote many centuries later. We’ve never seen anything like it,” says David Stuart, of the University of Texas, who deciphered the glyphs.

The glyphs appear to represent the various calendrical cycles charted by the Maya—the 260-day ceremonial calendar, the 365-day solar calendar, the 584-day cycle of the planet Venus and the 780-day cycle of Mars, as well as lunar semesters lasting 177 and 178 days. It seems that the Maya, too, had a way to deal with the extra day (think Leap Year).

This structure discovered by Saturno’s team was numbered 54 out of 56 total counted and mapped by a Harvard team in the 1970s. Thousands more at Xultún remain uncounted. And Nature News reports that:

The researchers identified 12 other etched or painted inscriptions in addition to those described in the Science paper, and analysis and excavation at Xultún continues. “We have 99.9% left to explore,” said Saturno. “We’re going to be working on it for many decades to come.”

Want more information? The work is funded by the National Geographic Society and is featured in the June issue of National Geographic magazine with a video on the project available here. The wall mural was photographed as a high-resolution panoramic gigapan, creating a zoomable view for users to explore the painting in detail. Enjoy! (You’ve got plenty of time, since the world isn’t ending any time soon…)