Science News

Puzzling Planets

How do planets form? What kind of atmospheres do they have? Two new studies about exoplanets, published today in the journal Nature, are providing new answers to those questions.

The first study describes a new planet found around the star HR 8799, which lies about 129 light years from Earth (you might even manage to find it with your unaided eye). The new planet, HR 8799e, joins three other known planets orbiting this star, all massive gas giants, forming something like a supersized version of our solar system. They all pull on each other gravitationally and the proximity of HR 8799e to its parent star has researchers scratching their heads.

How did these planets form? From Nature News:

Current theories suggest two ways in which a gaseous, dusty ring around a young star can form into gas-giant planets. In one — the ‘accretion’ model — small clumps of dust build up over millions of years to form a planet's solid core, which then pulls gases towards it. The other model, ‘fragmentation,’ suggests that small clumps of a gaseous disk form directly into planets over 10,000 years.

Dr. Bruce Macintosh of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, one of the authors of the paper, notes that there’s no simple model that can form all four of HR 8799’s planets at their current locations. “It’s going to be a challenge for our theoretical colleagues.”

Good luck with that!

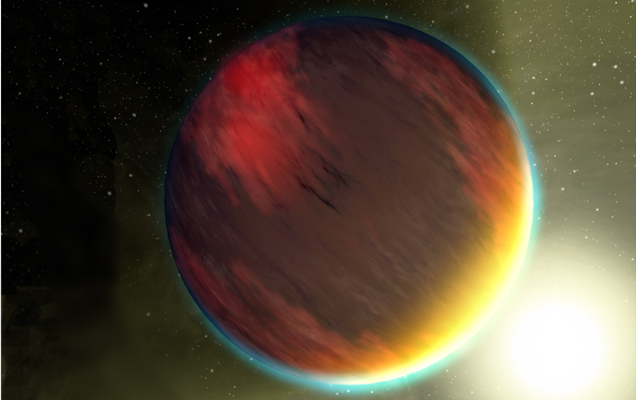

The second study also involves a gas giant, WASP-12b, that orbits extremely close to its star. Discovered in 2009 and located about 1,200 light years away, the planet has more carbon than oxygen, according to recent observations by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. This makes it the first carbon-rich planet every observed. From ScienceShot:

By studying the planet’s infrared glow, the astronomers discovered that its air abounds with the carbon-bearing molecules carbon monoxide and methane, implying that the planet could have carbide (a compound of carbon and metal) rather than silicate in its interior. If so, that makes it unlike any world in our solar system.

Although WASP-12b has no surface to host life, Earth-sized exoplanets may have formed around the same star (known as WASP-12a, go figure) billions of years ago. If detected, these smaller, rockier planets could also have carbon-rich atmospheres and interiors, meaning that for life to exist on these planets, it might have to survive with very little water and oxygen, and plenty of methane.

From Universe Today:

This suggests that there may be an entire range of carbon abundances available for planets. With the versatility of carbon for forming organic compounds, this enhanced abundance may lead to other, rocky planets covered in tar like substances rife with organics.

And you thought arsenic-laced bacteria was cool…