Science News

Space Friday: Small Things

Wait Just One… More… Second…

No, seriously. This year, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) is inserting an additional second to the last minute of December 31. Be sure not to make yourself look silly in front of all your friends by celebrating the New Year too soon.

To put it simply, the extra second is needed because Earth’s rotation is slowing down. Not by much, but over long periods, it adds up. Eventually, that cumulative error causes clocks to fall out of step with nature. For example, the Sun would no longer be at its highest at noon if left uncorrected (ignore for the moment that a regular variation already occurs—known as the Equation of Time—which has a similar short-term effect, but it averages out over the course of a year). In addition, the rate at which the planet’s spin is slowing isn’t constant. A major cause is friction caused by Earth’s rotation beneath the tidal humps raised in the hydrosphere by the Moon’s gravity, acting like an enormous brake. Because of this, full rotation of our planet takes a little longer today than it did a few centuries ago.

The Moon’s distance from Earth affects the strength of its gravitational pull, and because the Moon’s orbit is elliptical, changes in its distance ultimately factor into the amount of tidal friction experienced by our planet. Other influences include the redistribution of mass around Earth’s axis by either the melting of polar ice or majorearthquakes. It gets complicated, and sooner or later, a correction is needed so that both clocks and calendars are brought back into sync.

We’re already familiar with leap years, when February 29 is added every four years or so to keep our 365-day long calendars in step with Earth’s 365.242189-day orbital period around the Sun. Additional rules (and exceptions to those rules, such as “except on century years” and “except when the year is evenly divisible by 400”) are added for fine-tuning.

Some suspect it’s also just to mess with us.

But why does a telecommunications organization get to tell us what to do with our time? The ITU is a United Nations agency that—as its name implies—oversees global telecommunications standards, with far-reaching implications in communication, commerce, science, national security, and more. As ITU Secretary-General Houlin Zhao says, “Modern society is increasingly dependent on accurate timekeeping. ITU is responsible for disseminating time signals by both wired communications and by different radiocommunication services, both space and terrestrial, which are critical for all areas of human activity.” So when ITU speaks, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the U.S. Naval Observatory,Her Majesty’s Nautical Almanac Office, the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service, the World Meteorological Organization, the International Astronomical Union, and similar organizations listen.

Recently, the ITU considered abolishing the practice of adding a leap second, but decided to put the decision off until 2023, so enjoy that extra second… while it lasts! –Bing Quock

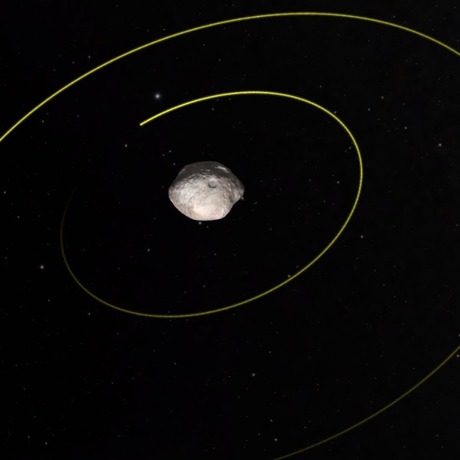

A Teeny Tiny Asteroid

Ready for the smallest asteroid ever studied in detail? 2015 TC25 is two meters (six feet) in diameter and was observed by four different telescopes last year when it sailed past Earth at 128,000 kilometers (79,000 miles), a third of the distance to the Moon.

“This is the first time we have optical, infrared and radar data on such a small asteroid, which is essentially a meteoroid,” says astronomer Vishnu Reddy, lead author of a new study in The Astronomical Journal. “You can think of it as a meteorite floating in space that hasn’t hit the atmosphere and made it to the ground—yet.”

Reddy and his colleagues report that even though 2015 TC25 is tiny, it’s one of the brightest near-Earth asteroids ever discovered. The team found that the asteroid’s surface is similar to a rare type of highly reflective meteorite called an aubrite. Aubrites consist of very bright minerals, mostly silicates, that formed in an oxygen-free, basaltic environment at very high temperatures. Only one out of every 1,000 meteorites that fall on Earth belong to this class.

The minute meteoroid is also one of the fastest-spinning, completing a rotation every two minutes.

Reddy believes that 2015 TC25 was probably chipped off from its parent, 44 Nysa, a main-belt asteroid large enough to cover most of Los Angeles. Asteroids are remaining fragments from the formation of the Solar System that mostly orbit the Sun in the main belt, between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Near-Earth asteroids are a subset that cross Earth’s path. So far, more than 15,000 near-Earth asteroids have been discovered.

“If we can discover and characterize asteroids and meteoroids this small, then we can understand the population of objects from which they originate: large asteroids, which have a much smaller likelihood of impacting Earth,” Reddy says. “In the case of 2015 TC25, the likelihood of impacting Earth is fairly small.

That said, the next small near-Earth asteroid could pose a risk to our world. “It’s especially important to study the physical properties of small near‐Earth asteroids because of the threats these objects pose to us,” says Stephen Tegler, co‐author of the study. “The meteoroid that caused injuries and damage in Chelyabinsk, Russia in 2013 was less than 20 meters (66 feet) in diameter.”

Follow the Chelyabinsk meteor and other small hard-hitting objects in Morrison Planetarium’s production Incoming!, now playing. –Molly Michelson

A Tiny Twist of Light

From tiny changes in our clocks to tiny asteroids in our solar system, we move to tiny effects in the transmission of light through the vacuum of space.

A strange property of space known as vacuum birefringence was predicted 80 years ago in a paper by Werner Heisenberg (yes, that Heisenberg, not this Heisenberg) and Hans Heinrich Euler (no, not that Euler, silly math geeks). But observational confirmation of the effect has eluded physicists and astronomers—until now!

The basic idea is that, in the presence of an intense magnetic field, the vacuum of space behaves effectively like a dielectric material, which means it can polarize light passing through it. (For you students of physics, that means that the old reliable Maxwell’s Equations remain old but not so reliable… And the Universe seems weirder and weirder.)

How intense a magnetic field? Well, let’s just say that the laboratory experiments on Earth weren’t having much luck creating an environment with strong enough magnets to observe the effect reliably. So when you can’t build it on Earth—look out in space! Neutron stars (the rapidly-spinning leftovers of massive stars that self-destructed in supernovae) have notoriously strong magnetic fields, nearly a trillion times stronger than what we experience here on Earth’s surface. Which makes them promising extraterrestrial laboratories for this kind of experiment.

The challenge is that they, like everything else in space, lie far, far away… And they’re intrinsically quite faint to boot. Observing a faint object made fainter by its distance, well, that requires an extraordinarily powerful telescope. Such as the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). A team of astronomers led by Roberto Mignani of INAF Milan (Italy) and the University of Zielona Gora (Poland) used the VLT to measure the polarization of light from the appealingly-named neutron star RX J1856.5-3754 (let’s call it “Rex”). They selected Rex because it lies a mere 400 light years from Earth—and that’s next door, as neutron stars go! (This video shows a zoom into the sky around Rex, giving a sense of how faint it is.)

Mignani and his team indeed detected polarization of Rex’s light, to a degree they claim cannot be explained without incorporating the effects described by Heisenberg and Euler. If they’re correct, then this marks the first observational confirmation of a prediction made eight decades ago. Tiny effects can take time to confirm. –Ryan Wyatt

Image: RX J1856.5-3754, ESO/Digitized Sky Survey 2