We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

The Moon is Shrinking!!

August 19, 2010

OMG. The Moon is shrinking.

NASA released word today that newly discovered cliffs in the lunar crust indicate the Moon shrank in the past and might still be shrinking today. A team analyzing images from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft published these results in the August 20 edition of Science.

Still shrinking? Don’t say goodbye to romantic nights yet. According to New Scientist,

The team calculates that the moon's diameter has shrunk by just 200 meters in the last billion years.

That’s just over 650 feet compared to a diameter of 2,159 miles.

New Scientist goes on to say that

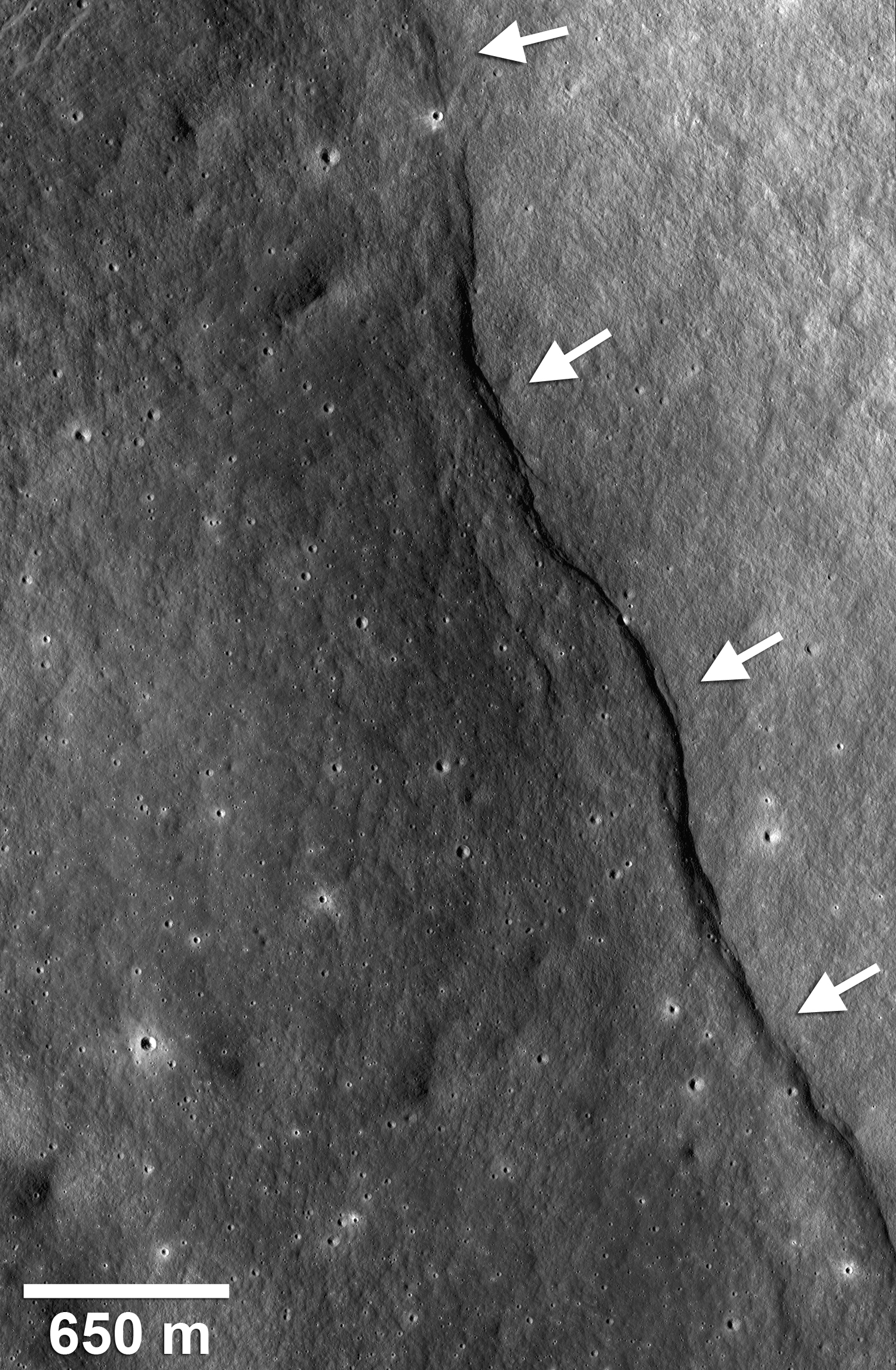

The shrinkage has wrinkled parts of the moon's surface like a raisin, creating pinched formations called lobate scarps.

The Guardian mentions that

Fourteen lobate scarps were identified, at sites as far apart as the lunar equator and near the poles. The features are so pristine scientists think they could be no more than a billion years old.

That’s pretty recent in the Moon’s 4.5 billion year history.

Lobate scarps provided the first clues of a shrinking moon. Astronomers had observed them for centuries, says the Bad Astronomer, and cameras took pictures of some during the Apollo missions in the 1970s.

The lobate scarps are formed by thrust faults—which “are formed when the core of the Moon contracts, and the surface crust is pushed together,” reports Astronomy Now Online.

Lobate scarps show up on other worlds in our solar system, including Mercury, where they are much larger. “Lobate scarps on Mercury can tower over a mile high and run for hundreds of miles,” said Thomas Watters of the Smithsonian Institute, lead author of the study. Massive scarps like these lead scientists to believe that Mercury was completely molten as it formed.

The Moon formed in a chaotic environment of intense bombardment by asteroids and meteors. These collisions, along with the decay of radioactive elements, made the Moon hot. The Moon cooled off as it aged, and scientists have long thought the Moon shrank over time as it cooled, especially in its early history. The new research reveals relatively recent thrust faults are part of that long-lived cooling.

During the next few years, the team hopes to use LRO's high-resolution Narrow Angle Cameras (NACs) to build up a global, highly detailed map of the Moon. This could identify additional scarps and allow the team to see if some have a preferred orientation or other features that might be associated with Earth's gravitational pull.

Furthermore, the team will compare the older Apollo images with the newer LRO ones to see if there has been additional shrinkage in the last 40 years.

Image: NASA/Goddard/Arizona State University/Smithsonian