Scientific Expeditions

2015 Philippine Biodiversity Expedition

In the spring of 2015, nearly 50 scientists conducted an intensive biodiversity assessment of the Philippines’ Verde Island Passage (VIP), an area thought to be the most biologically diverse marine ecosystem on the planet. This was the third such Academy-led expedition to the Philippines since 2011 and served as an important continuation of the institution’s decades-long scientific and conservation partnership with this nation of 7,000 islands.

To complete a thorough survey of the marine organisms that call the VIP home, the 2015 expedition team spent seven weeks scuba diving and collecting scientific specimens in a wide variety of habitats in the eastern half of the passage, including the deep, high-current waters around Verde Island itself. Topping the list of their many extraordinary discoveries were more than 100 species that are completely new to science, from nudibranchs and sea urchins to corals and fish. In addition, the scientists furthered their understanding of the roles that many organisms here play in their environments, and the vital connections that exist among seemingly distinct habitats. Both pieces of knowledge are critical to the conservation of this important ecosystem.

As Terry Gosliner, one of the lead scientists on the expedition, explains, “It’s thrilling to return to such an incredibly diverse region year after year. Whether we’re finding new species or adding to our understanding of previously known creatures and habitats, these expeditions help us pinpoint how and where to focus protection efforts.”

The Team

To ensure a comprehensive assessment of this important ecosystem, the 2015 expedition team included specialists in such diverse taxonomic groups as reef fishes, corals, barnacles, sea slugs, echinoderms, worms, tunicates, anemones, sponges, and algae. These scientists came from the Academy as well as a vast community of U.S and Filipino research and conservation partner institutions, including the National Museum of the Philippines, the University of the Philippines, the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, the National Fisheries Research and Development Institute, De La Salle University, the Smithsonian Institution, Old Dominion University, the University of Florida, Ohio State, UC Berkeley, University, San Francisco State, and the Bishop Museum.

Discovering a Living Fossil

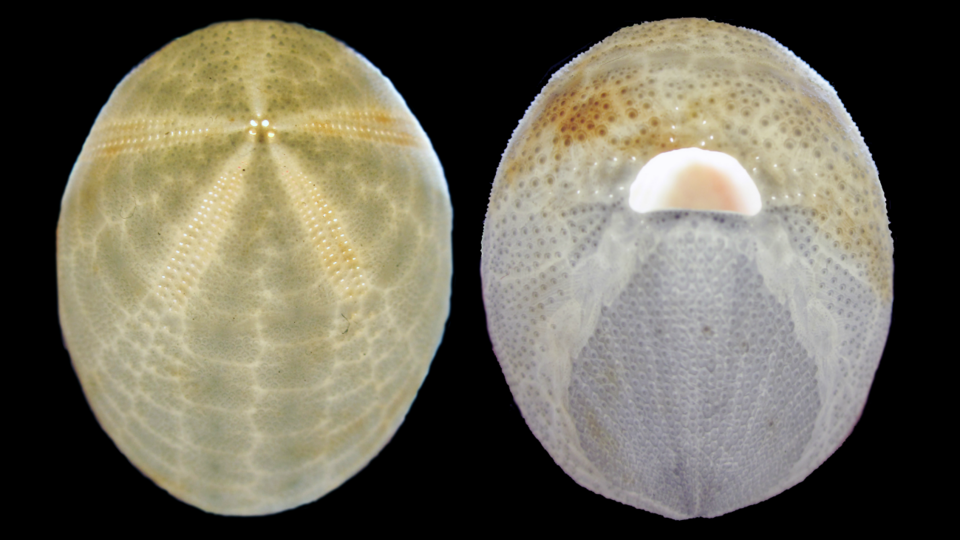

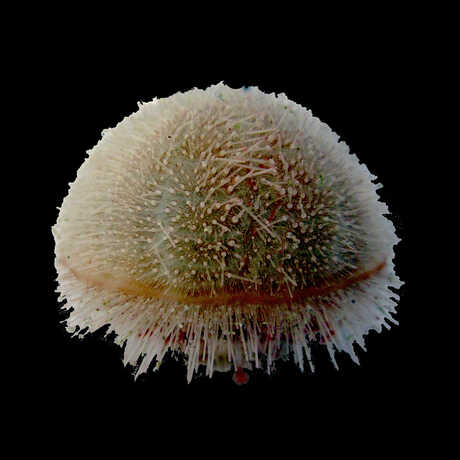

In 2014's expedition, scientists found the internal skeleton of a new species of heart urchin, an oblong echinoderm that makes its living cruising through the sand on the ocean bottom. Having found several more deceased specimens early in 2015, Rich Mooi, one of the Academy's curators of invertebrate zoology and an echinoderm expert, had begun to lose hope of finding a living specimen and knowing "what this cool beast actually looked like.”

Then, on a dive in April 2015, Dive Safety Officer Will Love came to the rescue with a live specimen he collected at a depth of 70 feet off the northern coast of the island of Mindoro. Mooi was thrilled with the find and marveled at the heart urchin’s pinkish-white spines, “like silk, or fine hairs.” While in the process of completing a formal species description, he and other researchers linked the new discovery with a long-lost relative from the Prenaster genus—a fossil species that roamed the seafloor roughly 50 million years ago.

Mooi sees this discovery as a prime example of why it's important for scientists to be here, exploring the rich waters of the VIP. “It’s critical we fill the gaps in knowledge about the life that thrives in the Philippines," he says. "You never know when you’re going to discover a living fossil among the corals."

Live from the "Twilight Zone"

Continuing their explorations of the some of the least explored real estate in the world, the expedition's team of deep divers once again plunged into the "twilight zone." This narrow band of depth, between 200 and 500 feet beneath the surface, is home to so-called mesophotic corals and other organisms adapted to this "half-light" environment. Because the twilight zone is beyond recreational diving limits and far above the deep trenches scientists explore when they have a submarine or an ROV, it just may be the least explored region on Earth.

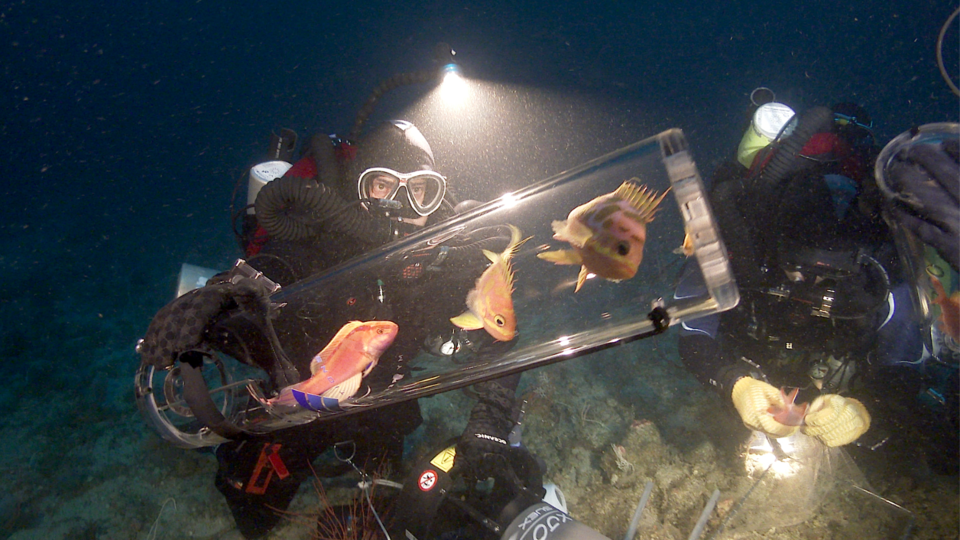

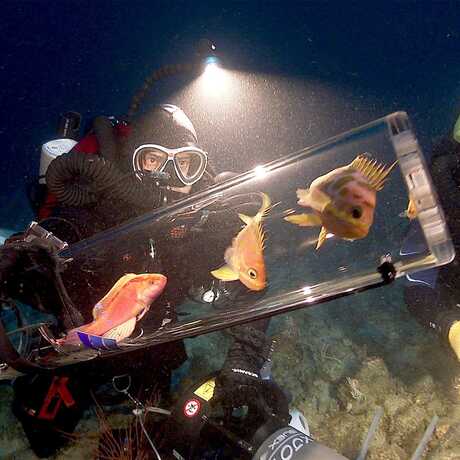

Reaching those extreme depths requires Academy divers to push the boundaries of both technology and the human body, using closed-circuit "rebreathers" that extend the amount of time they can spend underwater. The rate of new-species discovery in the twilight zone can top ten per hour, but scientists are typically afforded a scant 30 minutes in this light-starved region before they need to begin a multi-hour period of decompression on the way back to the surface.

Having discovered several new species in 2014, the team devoted a large portion of this expedition to collecting and bringing back live specimens—including 15 fish specimens, representing several recently discovered species, and a number of unusual species of corals and comb jellies (Lyrocteis imperatoris)—for display in the Academy’s Steinhart Aquarium.

"Most of what we observe and collect is so special—and often new to science—that we invented a custom decompression chamber to safely transport fishes to the surface," explains Steinhart Aquarium Director Bart Shepherd. "Seeing these animals in person will help the public learn more about why we need to explore and help protect the entire ocean, and not just what lives at the surface.” The Academy plans to open a new twilight zone aquarium exhibit in the summer of 2016.

Fostering a Community Around Conservation

An integral piece of the Academy's biodiversity research in the Philippines is the commitment to collaborating with Filipino colleagues and conservation partners and sharing their findings and recommendations with local communities. This happens before arrival and long after U.S.-based scientists have departed. In 2015, as on previous expeditions, expedition scientists worked alongside more than a dozen research and resource management colleagues from the Philippines as well as a team of Academy educators, who shared the expedition's findings with local community members, decision-makers, and conservation groups.

“The Academy doesn’t believe in ‘parachute science’ where researchers drop in, study wildlife, and leave,” says Terry Gosliner, one of the lead scientists on the expedition. “The world is changing before our eyes, and we need to work alongside global communities to build lasting, effective management strategies. Our scientists move beyond discovery and work with locals to develop plans that sustain threatened ecosystems while honoring the livelihoods of people who work and raise their families near the coastline.”

In addition, the scientific specimens collected during the 2015 field season—and the data derived from these specimens—will continue to inform both scientific understanding and conservation decisions for years to come. By sharing these findings with the scientific community and the general public, the expedition team hopes to strengthen the resolve to protect this rich and threatened ecosystem—and perhaps inspire the next generation of ocean explorers.

The mission of the Academy's Institute for Biodiversity Science and Sustainability (IBSS) is to gather new knowledge about life's diversity and the process of evolution—and to rapidly apply that understanding to our efforts to regenerate life on Earth.

Learn more about the expedition as it happened in this blog series hosted by Scientifc American magazine.