Scientific Expeditions

Thriving California: Caples Creek

Academy scientists hike through burned forest in the Caples Creek watershed.

Healthy, intact California forests help fight climate change and biodiversity loss—but they’re succumbing to wildfires at unprecedented rates. Prescribed burns may be good medicine.

Wildfires in California and much of the American West are growing larger and fiercer, and new strategies are urgently needed to protect human communities and vital forest ecosystems. One of the most promising solutions, however, isn’t actually new at all: the intentional application of fire, such as cultural burning, practiced by Indigenous communities for millennia. Journey into the remote Caples Creek watershed southwest of Lake Tahoe, where scientists and forest managers from across the state are investigating the relationship between prescribed burns and enhanced biodiversity—and how both can boost forest resilience in the future.

Need a Caples Creek recap? Check out our press release from the beginning of the project and follow #ThrivingCalifornia on our social media channels for the latest.

Fighting fire with fire

As record-breaking wildfires raged across California in 2017, the California Academy of Sciences and the US Forest Service embarked on a unique collaboration. The Academy’s Jack Dumbacher, Durrell Kapan, and Peter Roopnarine connected with the Forest Service’s Pat Manley, research scientist with the Pacific Southwest Research Station, and Becky Estes, Central Sierra Province Ecologist, to explore the Caples Creek watershed, a 32-square-mile swath of land along the South Fork of the American River that had miraculously managed to avoid both wildfire and development for nearly a century.

With a prescribed burn scheduled for the area in fall 2019, the timing was perfect for the team to test their theory: That the selective application of fire to the landscape not only makes forests more resistant to future wildfires by removing highly flammable fuel, it serves to maintain or enhance forest biodiversity, too.

The Caples team and colleagues catch up after a morning of field surveys. (From left: Jack Dumbacher, Durrell Kapan, Paul Meznarich, Pat Manley, Duane Nelson.)

Capturing the calls of the wild

Since biodiversity is essential to a forest’s recovery after a fire, “our idea was to use it as a metric for the health of the forest both before and after the burn,” explains Dumbacher, the Academy’s curator of ornithology and mammalogy. Birds, whose presence—or absence—can reveal how well an ecosystem has bounced back after a disturbance like fire or drought, serve as a reliable biodiversity bellwether. And so the team set out to count them.

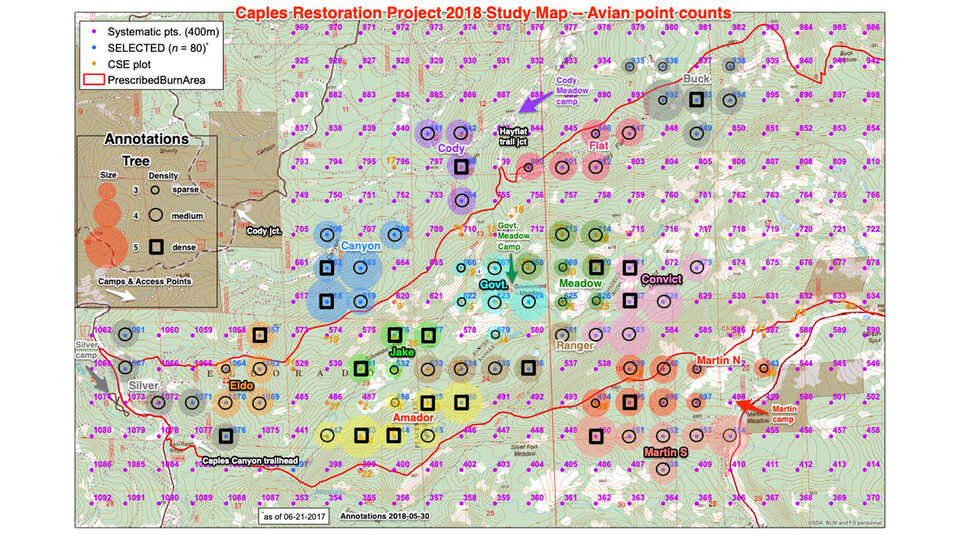

Every June between 2017 and 2022, the Academy team and their Forest Service colleagues established their bird count base camp in the heart of the Caples Creek watershed study area. Over the course of three weeks, they criss-crossed thousands of acres of rugged terrain to conduct the counts at 82 sites specially selected by Manley, a research ecologist specializing in biodiversity. “Pat has been doing bird surveys in the Sierra Nevada and Northern California for over 30 years,” says Kapan, a senior research fellow at the Academy. “She selected sites both inside and outside the planned burn area that represented a broad spectrum of terrain and habitat types and could be surveyed by a single trained observer in a day."

This map shows the location of survey sites organized into survey “clusters” inside and outside the Caples study area.

The early birder gets the data

Field work, however, would follow the birds’ circadian rhythms, not the scientists’, and the surveying would start long before sunrise.

During the June expeditions, the team expanded to include five or more observers trained in bird identification. They’d wake up at 3:15 am, grab some hot coffee and a quick bite at the base camp, and then fan out to their respective survey sites, often bushwhacking miles in the pitch dark to arrive at the first site just after dawn. At each site, the protocol was the same to ensure scientific consistency: Keep quiet, stay in one spot, and tally up all the birds heard (and less often seen), noting their distance within or outside a 100-meter radius. Each observation was a valuable data point, telling a unique story about bird behavior, from establishing territory to nesting and fledging young. After finishing up the day’s surveys around 9:15 am, the team would attend to additional field duties and then return to camp to compile their data and exchange stories about the day’s observations and adventures.

“We’d cook dinner together at 5:30 or 6 pm so we could be in bed by 8-ish—the sun would still be up if we did it right—and then we’d do it all over again the next day,” Dumbacher recalls.

By the conclusion of each expedition, every site would have been surveyed three times by three different people at different times of the morning and days of the month to provide a representative, 360-degree picture of bird biodiversity.

Jack Dumbacher at a Caples survey site with an acoustic recording unit (ARU) in the foreground.

The birds are back in town

Having completed their sixth annual expedition in June 2022, the team is now focused on translating the Caples data points into a cohesive story. With collaboration from Forest Service scientist and statistical modeling expert Angela White, postdoctoral researcher Mary Clapp is leading the analysis that will result in a publication of the research—which features one highly encouraging finding.

“It appears that the Caples burn in 2019 did enhance forest resilience,” Kapan says. “We saw a substantial increase in the number of bird species breeding within the study area after the fire came through,” Clapp adds. The return of the birds—including a few species that thrive in burned areas, like the black-backed woodpecker—is scientific shorthand for a return of biodiversity, indicating that using fire to combat fire can be beneficial for at-risk forests and their inhabitants.

Still more evidence of the preventive power of prescribed burns would appear on the scene two years later.

A clutch of junco eggs in a well-concealed nest in the Caples Creek watershed.

Learning from Caldor

The Caldor Fire put the effectiveness of the intentional Caples burn into sharper relief. As the wildfire bore down on the Caples Creek watershed in October 2021, it largely leapfrogged the Caples watershed—and yet scorched the forested areas around it. While continued fieldwork to measure the response to the two burns is still required, it appears that intentionally burning the study area in 2019 effectively shielded it from Caldor’s wrath. “Resilience is the ability of an ecosystem to maintain its identity after a disturbance,” Roopnarine, the Academy’s curator of geology, says. “If a forest stays a forest after a fire and doesn’t devolve into a shrubland type, like chaparral, we’d call that forest resilient.”

Decades of wildfire suppression in the West have contributed to a dangerously overgrown Sierra: green, yes; resilient, no. As the climate crisis changes the behavior of fire, we also need to change our thinking around forest management—and understand that fire as a management tool can be highly effective in improving forest resilience and reducing the risk of impacts from fire. “We need to simultaneously bolster forest resilience and biodiversity by intentionally applying fire to the landscape when it is safe to do so,” Kapan says.

“Some people still think fire is bad, period,” Dumbacher adds. “But the data we have show that there is life after fire."

Summer Systematics Institute interns Hailey Schmidt (left) and Natalie Beckman-Smith collect plant data in the Caples study area.

Partner profile: The US Forest Service

Collaboration is central to the Academy’s mission—and is reflected in our full and equal partnership with the US Forest Service. We’re deeply grateful to our colleagues at the Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Research Station and Region and Eldorado National Forest for bringing their support and diverse expertise to the Caples study.

We’re particularly grateful to Pat Manley, whose fierce dedication to studying and conserving our forests—and generosity in advancing this collaboration—serves as an inspiration to Academy scientists and interns alike. “Partnering with Academy scientists and staff has helped bring new perspectives and skills to our research to restore forest resilience,” Manley says. “They have helped new audiences to learn about the challenges that forest managers are facing and the incalculable value of our forests."

What's next

- The team will return to the study area in June 2023—and, funding permitting, subsequent Junes after that—to continue measuring the forest’s and birds’ evolving response to both the Caples burn and Caldor Fire.

- Sarah Jacobs, the Academy’s assistant curator of botany, is collaborating with Forest Service scientist Becky Estes to describe pre- and post-fire plant diversity in the study area, an effort that will help to characterize the impacts of different fire severities on plant communities. In addition, they are integrating on-the-ground data collected in the field with satellite imagery of vegetation conditions to relate the two types of data to one another.

- Dumbacher, Kapan, and Clapp are working with Google engineers to integrate data from acoustic recording units (ARUs), devices that automatically detect and record bird vocalization. Deployed by the team across the study area each year since 2018, ARUs enhance our understanding of how the bird community is changing in response to fire and over time in general.

Where: Caples Creek watershed (view map in iNaturalist)

When: June 1-20, 2022

Why: Biodiversity surveys in fire study area

Who: Academy scientists Jack Dumbacher, PhD, Sarah Jacobs, PhD, Durrell Kapan, PhD, Peter Roopnarine, PhD; US Forest Service scientists Mary Clapp, PhD, Becky Estes, PhD, Pat Manley, PhD, Angela White, PhD; intern Mark Schulist.

Donations of all sizes power Academy science in the Sierras and around the world.