Steinhart Aquarium Is 100! Here Are 10 Times We Were First

Bart Shepherd is senior director of Steinhart Aquarium and an expert chronicler of Academy lore. This post contains excerpts from his new book, The Spectacular Steinhart Aquarium, on sale now at the Academy Store.

On September 29, 1923, more than 5,000 people lined up to enter Steinhart Aquarium on its opening day. This was a time before commercial air travel and color photography were commonplace, so our aquarium showcased creatures people would likely never otherwise encounter, from colorful coral reef fishes to unimaginable life forms like blind river dolphins and four-eyed fish.

Over the next hundred years, Steinhart Aquarium and the Academy would evolve into a world-class organization that welcomes over a million guests each year and advances science and conservation—all under one Living Roof. Read on for 10 of my favorite Steinhart firsts.

Alvin Seale, the first superintendent of Steinhart Aquarium, observed that Artemia, a small crustacean living in the salt ponds near San Mateo was readily eaten by many difficult-to-keep marine and freshwater fishes. Brine shrimp—also known colloquially as "Sea Monkeys"—are now extensively used in aquaculture, and are produced in the Great Salt Lake, a number of locations in Central Asia, and of course, San Francisco Bay, where it all started.

Eugenie the dugong was harpooned in Palau, purchased for $20 by Stanford ichthyologist Dr. Robert Rees Harry, and flown to Steinhart for emergency treatment. Sadly, he died about one month after arrival from an infection in the harpoon wound—but not before achieving worldwide renown from coverage in Time magazine and newsreels of the day.

Steinhart Curator and Pathologist Robert Dempster pioneered the prophylactic use of the chemical compound copper sulfate to treat Oodinium parasites that commonly afflict marine animals.

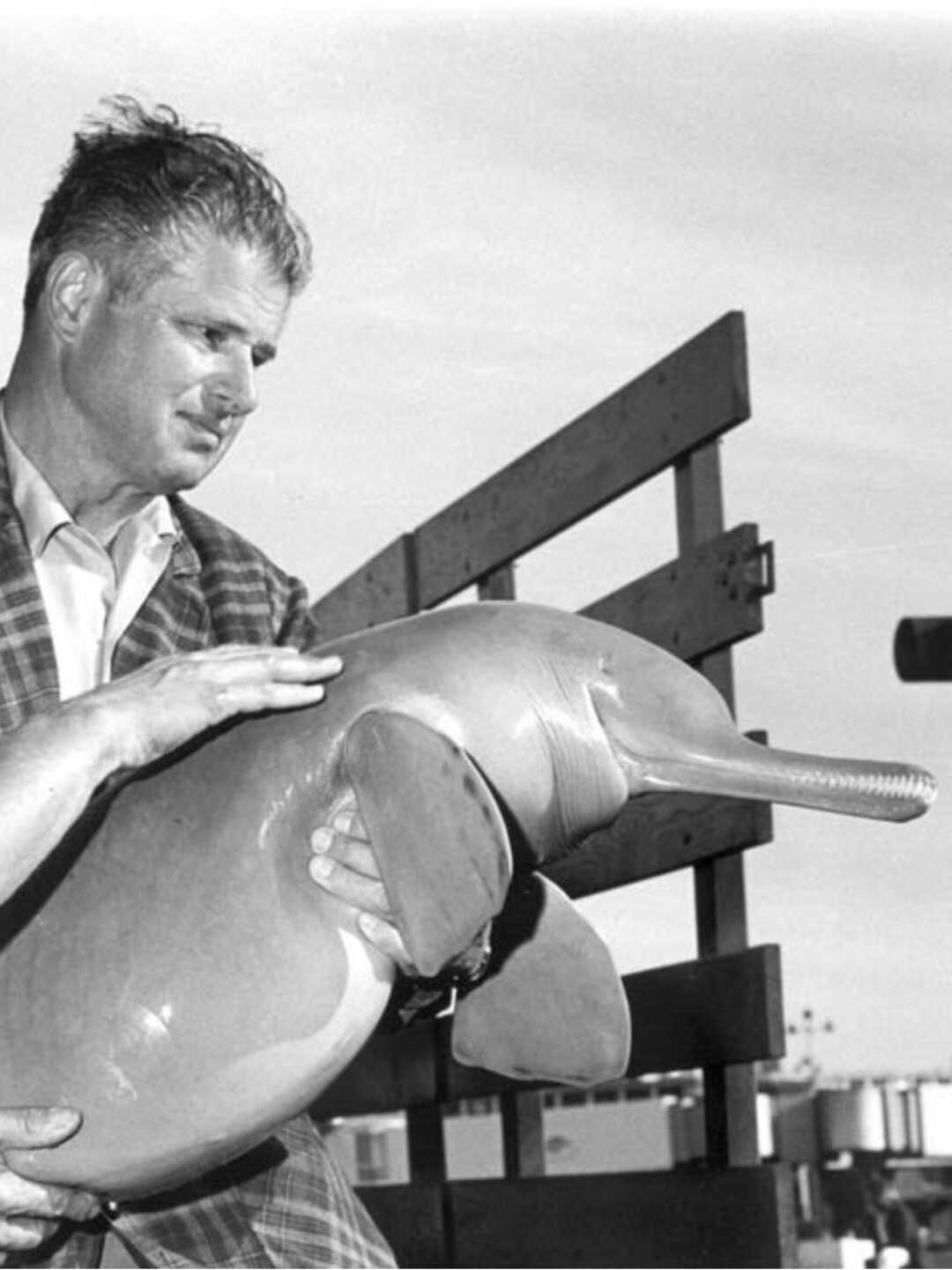

Steinhart Superintendent and Curator Earl Herald obtained a susu, or blind river dolphin (Platinista gangetica), while on expedition in Pakistan. Herald observed that the animal swam on its sides, one of many unusual adaptations that helped his susu research make the cover of Science magazine.

In 1977, the Fish Roundabout (pictured at the top of this post) put our visitors in the center of the action and surrounded them with a never-ending carousel of open-ocean fishes. This influential exhibit, the first true ring-tank, perfected an earlier Japanese design. (The exhibit was also, apparently, the center of another kind of action, having been voted the "Best Place to Make Out" by San Francisco Bay Guardian readers.)

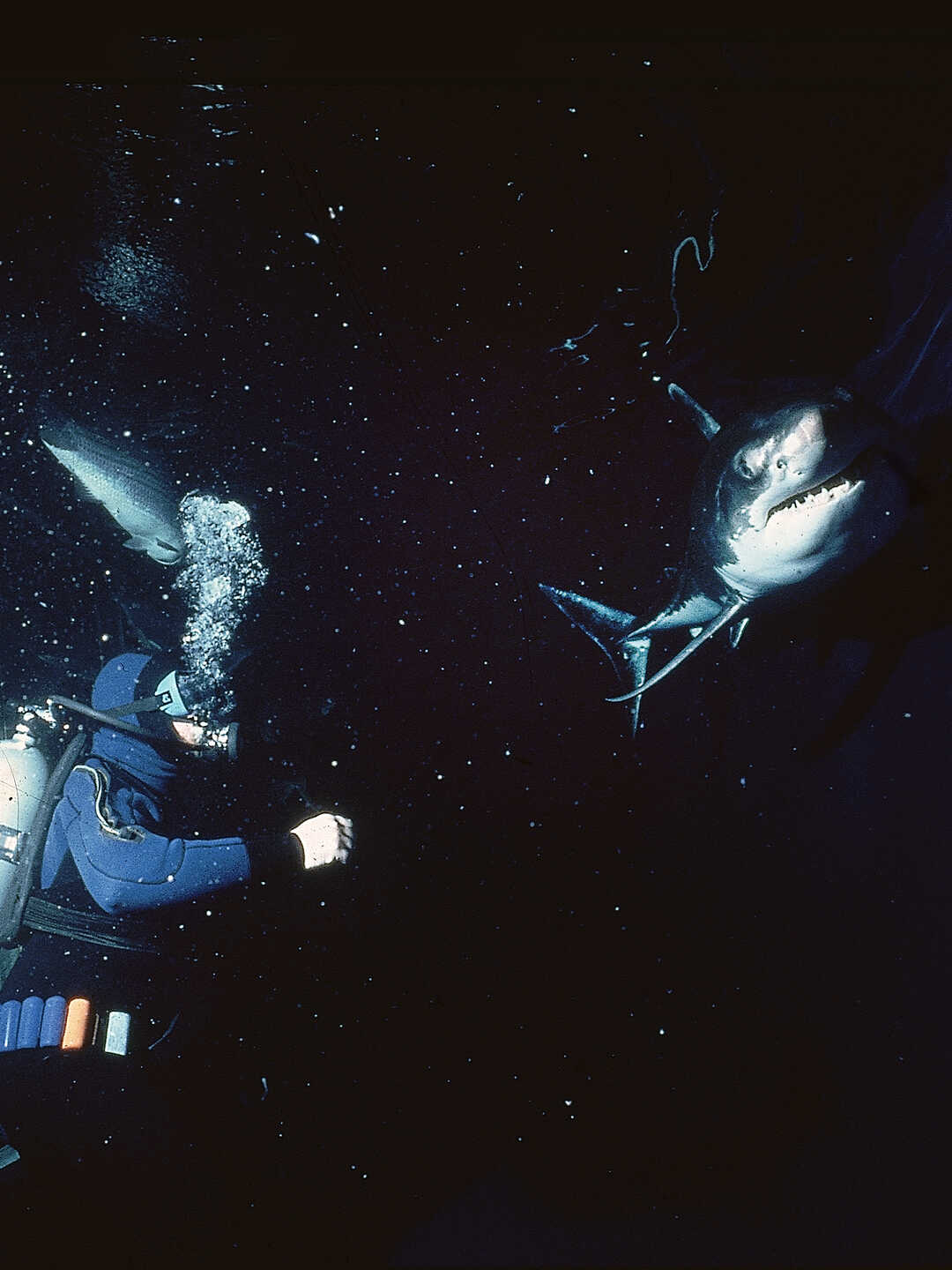

With the new Fish Roundabout, Steinhart Aquarium could display large sharks and joined a race to be the first aquarium to successfully display a great white.

Sandy the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), shown below with former Steinhart Director Dr. John McCosker, attracted more than 40,000 visitors during the few days that she inhabited the Fish Roundabout. She was released into the wild following her successful, but short, stint in the aquarium.

A YouTube commenter humorously described our Burmese vine snakes (Ahaetulla fronticincta) as "judgmental shoelaces," and they're not altogether wrong. These waifish reptiles are unique in that they live in trees but prey on fish. Find them on exhibit in Water Planet.

We collected pygmy seahorses (Hippocampus spp.) in the Philippines in May 2014 and successfully transported them to San Francisco within 36 hours. They started breeding pretty quickly, which is a good indication that they're acclimating to their new habitat. Shortly after that, the males began producing babies, something we never predicted would happen—and something nobody had ever witnessed before.

By replicating conditions in the wild, our Coral Regeneration Lab (CoRL) has successfully elicited coral spawning events five years in a row and counting—and our Acropora hyacinthus babies are thriving. Check out Assistant Curator of Invertebrate Zoology Dr. Rebecca Albright's report on CoRL's remarkable progress.

Bringing live fish up to sea level from the depths of the "twilight zone" (100-500 below the surface) is critical for studying and exhibiting little-known species—but also a major technical challenge. That's why Steinhart staff developed and patented a portable decompression chamber, dubbed "SubCAS." You can see a replica of this device on exhibit in Twilight Zone: Deep Reefs Revealed.

For more Steinhart centennial stories, follow Bart Shepherd on X (formerly Twitter) at @SteinhartBart, and keep tabs on our YouTube Playlist, where new videos will be released every week.