Swoon for Our Moon Rock

Nestled in an understated vacuum-sealed case just outside Morrison Planetarium is a priceless piece of space history: a Moon rock.

Just a few centimeters across and clocking in at a whopping 3.7 billion years old, the Academy’s Moon rock—descriptively named Sample 70035—serves as a physical reminder of NASA’s iconic Apollo expeditions and what these forays taught us about outer space, our Moon, and our planet’s health.

The Academy is proud to be one of a handful institutions in the state that publicly displays a Moon rock sample. Learn more about this special rock during your next visit—and between September 4 and 9, check out a pop-up exhibit on NASA’s upcoming expedition to Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Our little chunk of lunar crust was collected in December 1972 on Apollo 17, the last mission to put humans on the Moon. Over a span of 12 days, astronauts Harrison Schmitt and Eugene “Gene” Cernan gathered over 250 pounds of rock and soil samples.

This particular sample was located on the rim of a crater between the Sea of Tranquility and the Sea of Serenity, near where the first humans walked on the Moon three years earlier.

Astronaut Harrison Schmitt (left) allegedly picked up and examined Sample 70035 with his bare hands on the Apollo 17 Command Module, perhaps gaining permission because of his training as a geologist.

© NASA

Despite its exotic origin, our Moon rock contains materials commonly found on Earth: It is composed of ilmenite basalt rock and is coated on the bottom with glass, according to the NASA Lunar Sample Compendium.

Once transported to Earth, the original Sample 70035 was split into several pieces and distributed to partner organizations, with subsample 70035.18 eventually making its way to the Academy.

Before it was split into pieces, Moon rock Sample 70035 weighed as much as a medium-sized watermelon—despite measuring only a few centimeters across. © NASA

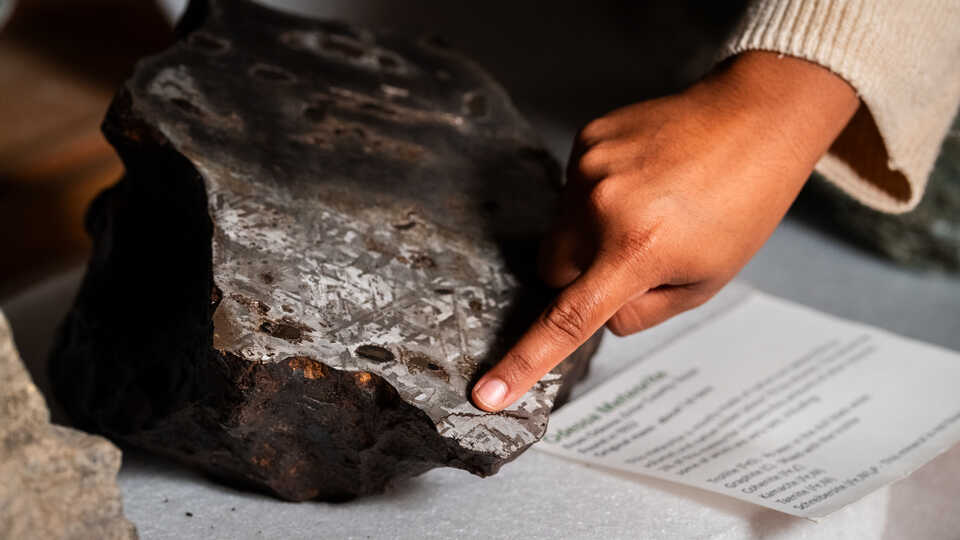

Collections Manager Crystal Cortez points to the patterns specific to geology samples from space, including this meteorite composed of iron and nickel. Gayle Laird © 2024 California Academy of Sciences

Apollo 17 provided the first opportunity for a geologist—Harrison Schmitt—to visit the Moon, and researchers used his particular expertise to determine whether ancient rocks collected from the Moon’s crust showed evidence of volcanic activity. For geologists, these lunar samples offer vital clues into the Moon’s development over billions of years.

“Planetary geologists have used these lunar samples to support the leading theory that our Moon originated as an offshoot of a collision between the Earth and another planet,” adds Cortez.

Using shovels, tongs, rakes, hammers and other trenching tools, Schmitt and his fellow astronauts chipped away at nearly 600 pounds of lunar rocks over the span of three years and six different Apollo missions. Many samples were taken from the Moon’s surface, but several were extracted from the Moon’s core, offering geologists vital clues into the Moon’s development over the eons.

“A portion of [this] rock will be sent to a representative agency or museum in each of the countries represented by the young people in Houston today,” said scientist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt, upon returning from the Apollo 17 mission. “We hope that they—that rock and the students themselves—will carry with them our good wishes, not only for the new year coming up but also for themselves, their countries, and all mankind in the future.”

The vast majority of the rocks are now under the care of NASA, which uses the specimens for scientific research and education. Even at the Academy, where we’ve hosted the specimen since 2015, our Moon rock sample is technically a loan from NASA with a mandate to always display it for public education.

Sample 70035 is kept in a vacuum-sealed case custom-made by Academy preparator Peter Gibbons. Though it’s unknown when the Moon rock was last handled, the specimen is encased in pure nitrogen gas to ensure it does not degrade in Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere.

Gayle Laird © 2024 California Academy of Sciences

Though most lunar samples are closely tracked by NASA, a handful have been lost over the years as astronauts and American politicians donated samples to other countries, world leaders, and even family members. A dedicated cadre of moon rock investigators continues to search for missing lunar samples to this day. (If you have any leads, by the way, send an email to moonrocks@collectspace.com.)

55 years ago, Armstrong and Aldrin’s moonwalk transformed a generation of Earthlings into space fans and science-lovers. Today, our horizons extend well beyond our own Moon.

“Sending the trained eyes and mind of a geologist to the Moon during Apollo 17 allowed us to unlock the secrets of its distant past in a way no robotic explorer could have,” says Ryan Wyatt, senior director of Morrison Planetarium. “But we humans are fragile creatures, and our great successes will likely come in using machines to investigate environments more distant and hostile than anything any human has ever experienced.”

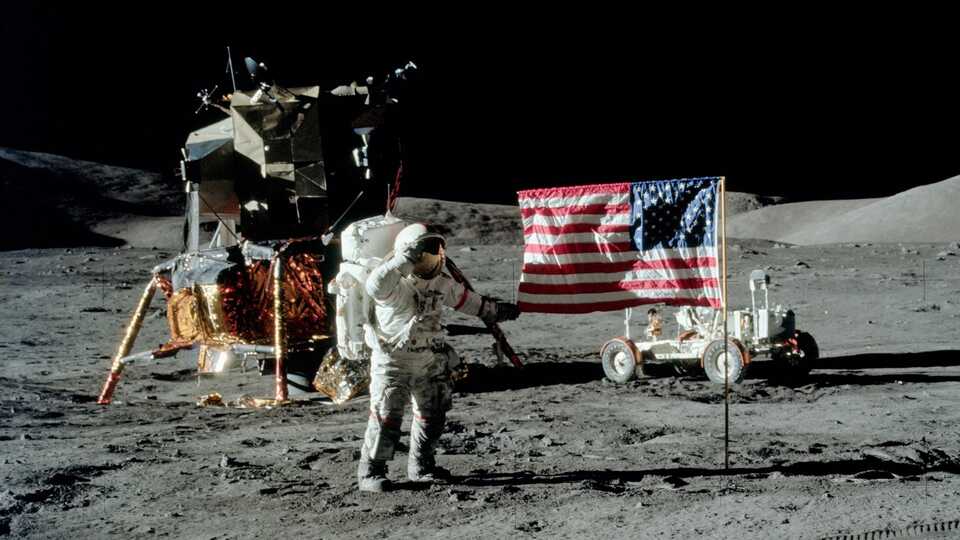

Apollo 17 astronaut Eugene Cernan salutes the American flag on the Moon, near the mission's Lunar Module "Challenger." © NASA

Unboxing the Europa Clipper spacecraft at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. © NASA/Kim Shiflett

A new pop-up exhibit, “Voyage of Europa Clipper: Exploring an Alien Ocean,” will make a brief cameo at the Academy from September 4–9, bringing a hands-on opportunity to learn about Jupiter’s moon Europa and NASA’s upcoming mission to explore it. By placing an advanced, unmanned spacecraft in orbit around Jupiter, NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory will be able to study Europa’s icy surface from afar and potentially identify conditions suitable for life.

Perhaps in a decade or two, a rock from an alien moon will inspire a new generation of Academy guests—some of whom may boldly go where no one has gone before.